In recent months, a series of ostensibly peace-oriented initiatives have unfolded across the Middle East. In Lebanon, an international-backed plan seeks to disarm Hezbollah, the powerful Shia armed group, under the banner of “national unity and stability.” In Syria, the U.S. is midwifing a deal to integrate the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) into the Syrian national army, framed as a step toward ending years of conflict.

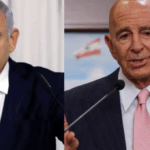

At first glance, these efforts seem to signal progress toward peace. However, in reality, these initiatives appear to be less about genuine reconciliation than about advancing a grand strategic plan that favors Israel. By dismantling the last effective Muslim armed non-state actors to Israeli regional dominance, these “peace” plans align neatly with long-standing objectives of the Greater Middle East project – a vision that has sought to redraw the region’s political landscape to the advantage of Tel Aviv. Central to this story are two key players operating behind the scenes: Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose public anti-Israel rhetoric masks his quiet collaboration, and U.S. envoy Tom Barrack, who has been orchestrating these moves through diplomatic back-channels.

Orchestrated ‘Peace’ Plans in Lebanon and Syria

In Lebanon, Prime Minister Nawaf Salam’s government shocked the country by ordering the army to draft a plan for disarming all militias by year’s end, a measure clearly aimed at the Shiite resistance movement Hezbollah. Washington eagerly endorsed the move – U.S. officials hailed it as a bold assertion of Lebanese sovereignty, with U.S. envoy Tom Barrack calling the disarmament decision “bold, historic, and correct”. The Lebanese cabinet has already begun dismantling Hezbollah positions in the south under UN supervision. This has been sold domestically as reclaiming the state’s monopoly on force. However, Hezbollah and its allies see it as a direct assault on the country’s only credible defense against Israel. “This is not about ‘stability’ or ‘sovereignty.’ It is about stripping Lebanon of its only credible shield against Israel’s constant aggression,” wrote one Lebanese commentator, noting that the army is now being ordered to “neutralize the only force that [truly] does [fight Israel]”. Indeed, even many Lebanese who criticize Hezbollah acknowledge that its well-armed fighters have deterred Israeli invasions since 2006. Removing this deterrent under the pretense of “peace” would, they warn, leave south Lebanon exposed – effectively handing Israel a victory it couldn’t win militarily.

In Syria, a parallel drama is unfolding with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the U.S.-allied militia that battled ISIS. After over a decade of civil war, a new interim government in Damascus (dominated by the Islamist faction Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, HTS) reached a deal in March 2025 to integrate the SDF’s fighters into the Syrian national army. On paper, this was a reconciliation effort meant to reunify Syria. But here too, the context raises questions. This deal came amid a U.S. military drawdown in Syria and intense pressure from neighboring Turkey, which views the Kurdish YPG (core of the SDF) as a terrorist extension of its own insurgent PKK. Washington quietly brokered and pushed the March agreement: analysts note that Kurdish interests were ultimately “overtaken by the larger US goal of fostering ties with Syria’s new regime, likely with the goal of encouraging it to establish relations with Israel”. In other words, the SDF’s capitulation was part of a bigger picture – removing an obstacle to a post-war regional alignment. The U.S. ambassador and envoy for Syria, Tom Barrack, shuttled between the Syrian government and the Kurds to iron out the details, urging the SDF to accept that “Syria is one country, one army, one people” and to lay down their arms in exchange for integration. Barrack praised Damascus’s “great job” presenting terms and said he hoped the SDF would join the national army quickly. Notably, this U.S.-steered plan came with an implicit expectation: a unified new Syrian state would eventually make peace with Israel. Barrack himself downplayed rumors of imminent Syria-Israel talks, but affirmed that regional normalization with Israel “should happen, and it’ll happen… slowly” as trust builds.

Dismantling Deterrents for a “Greater Israel” Vision

Stripping Hezbollah and the SDF of their weapons aligns closely with the long-term objectives of the “Greater Israel” project often discussed in regional power circles. This concept refers to a strategic vision – attributed to U.S. neoconservatives and Israeli expansionists – to reshape the Middle East so that Israel can integrate economically and militarily dominate without facing potent resistance. In the early 2000s, Turkey’s own Recep Tayyip Erdoğan infamously boasted, “Turkey has a duty in the Middle East… We are one of the co-chairs of the Greater Middle East and North Africa Initiative (BMENA). And we are carrying out this duty.” At the time, Washington described BMENA as promoting democracy and stability. But it was widely seen in the region as Washington’s strategic initiative to re-engineer the region under Israeli tutelage.

Just months before becoming a co-chair of this project, Erdoğan delivered a speech at Harvard on January 30, 2004—shortly after assuming the role of prime minister. In his speech, he expressed that Turkey “sincerely wishes for the United States to be successful in Iraq and provides multifaceted support” and stated that “Turkey will not consent to anyone threatening Israel’s right to exist.

Today’s “peace” maneuvers fit this template. By eliminating armed resistance in Lebanon and Syria, Israel can advance their regional agenda unopposed. The so-called Promised Land or Greater Israel project, once dismissed as a conspiracy, seems to inch closer to reality with each militia destroyed or disarmed. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has openly tied such disarmament to Israel’s future. In a recent interview, Netanyahu offered Israeli “support” to Lebanon if it moves to disarm Hezbollah, framing it as help for Lebanese sovereignty.

Hezbollah’s leaders themselves see the disarmament plan as part of a broader design to weaken all who resist Israel. “The greater [Israel] is on the way,” a member of Lebanon’s parliament warned in response to the cabinet decision, implying that an unarmed Lebanon could be coerced into submission or even partition. A Lebanese-American analyst was even more blunt: “If this plan goes forward, Lebanon as we know it will vanish… It will be just another corner of the ‘Greater Israel’ map,” he wrote, arguing that Hezbollah’s weapons are the only deterrent to an Israeli takeover of south Lebanon. This assessment underscores that from the perspective of many in the Arab world, calls for “peace” that involve Arabs disarming are viewed as stratagems to secure Israel’s regional supremacy.

In Syria, too, the grand strategy is evident. The fragmentation of Syria into spheres of influence – with Turkish-backed Islamists in the northwest, U.S.-backed Kurds in the northeast, and Israel effectively seizing a “buffer” zone in the south – has long been seen as advantageous to Israel’s security. Notably, once the HTS-led rebels ousted the Iran-aligned Assad government in late 2024, Israel wasted no time in extending its reach: Israeli forces crossed the UN-patrolled Golan Heights zone and occupied territory in southern Syria, even declaring their hold on strategic Mount Hermon permanent. Under the old Syrian regime, Israel faced an Iranian-backed army and Hezbollah fighters next door; under the new fragmented order, Israel faces no comparable threat. That was stage one of a broader design. Stage two targets the SDF: as the last cohesive, battle-tested force on the field, its continued autonomy is cast as a barrier to Israel’s maximalist “Greater Israel” project.

By demobilizing Hezbollah and the SDF, Israel with the help of the U.S. is taking out the remaining “insurance policies” that regional states or communities had against unchecked Israeli power and ambitions. The result, if these moves fully succeed, would be a Middle East where no independent armed force exists to deter Israeli military action – a key prerequisite for any broader expansionist or hegemonic project.

Land Forces: Israel’s Achilles’ Heel

A crucial piece of the puzzle is Israel’s relative weakness in protracted ground warfare due to the weakness of its land forces, which makes it extremely costly and difficult for the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) to directly occupy and sustain an occupation.

Israel maintains a technological and airpower edge, but its land forces are neither large nor resilient enough to sustain lengthy occupations or counterinsurgencies without sustaining substantial casualties and political blowback. This reality has driven Israel to seek “security architectures” that push others—local proxies or international forces—to do the dirty work on the ground to neutralize threats. For instance, Israel used different proxies—including Kurds and jihadist groups such as HTS and ISIS—to topple Assad, who, like Saddam’s Iraq and Gaddafi’s Libya, has been a staunch enemy of Israel since his father’s era. Israel even used these groups against each other in Syria.

History bears this out. During the 2006 Lebanon War, the IDF launched a ground invasion aiming to wipe out Hezbollah’s rocket squads. Instead, Israeli troops got bogged down and suffered embarrassing setbacks. Hezbollah’s well-dug fighters ambushed Israeli armored columns, inflicting losses; despite 34 days of fierce fighting, Israel could not decisively defeat Hezbollah’s guerrillas. The war ended in stalemate and a UN ceasefire, with Hezbollah’s leadership boasting that Israel was like a “spider web” – seemingly strong but unable to absorb pain. Indeed, analysts noted that the 2006 war “highlighted [Israel’s] casualty sensitivity: Hezbollah, unlike Israel, was willing to sacrifice”. Israeli society’s low tolerance for sustained troop casualties (so-called “casualty sensitivity”) has been documented by military analysts. In both Lebanon and earlier in Gaza, public pressure over fallen soldiers forced Israel to curtail ground operations and seek other solutions. One U.S. strategic study bluntly concluded that “occupying Lebanon is a nonstarter” for Israel – any protracted campaign would be untenable as Hezbollah could simply melt away, wait out the assault, and bleed Israel over time. The same logic applies to Gaza: Israeli officials openly fretted in late 2023 about the quagmire of re-occupying Gaza, knowing that urban warfare could sap their military and international standing. It is almost two years on, and despite relentless bombing and genocidal warfare methods, Israel has not been able to capture Gaza

Because of these limits, Israel has pivoted to an indirect approach: rely on airstrikes and high-tech weaponry to weaken foes, while pressuring international partners to handle ground security. Instead of sending Israeli infantry to clear Hezbollah out of Lebanese villages (which proved futile in 2006 and quite limited in 202-25), Israel now cheers for the Lebanese Army and UN peacekeepers to do it via the new disarmament plan.

Israel’s expansionist ambition under the so-called “Greater Israel” project extends beyond Lebanon and southern Syria. In the “Promised Land” conception, parts of today’s Kurdish territories are also included. Many assume—or claim—that Israel and the Syrian Kurds are allies and mutually supportive; this is not correct, even if it can appear so on paper. Against this backdrop, there is enduring potential for friction—and even conflict—between Kurds and Israel, particularly between Kurds in Syria and Israel.

By pushing for militias to disarm and integrate into state forces, Israel helps ensure that any future conflict pits it against national armies, which are typically constrained by politics and international pressure. National armies—such as Lebanon’s, or a reconstituted Syrian army without heavy or sophisticated weapons under Israeli conditions—can be cajoled or deterred through state-to-state diplomacy in ways guerrilla movements cannot. They are also generally weaker and less motivated than ideological resistance groups fighting on their home turf.

In effect, Israel is outsourcing its ground security to its Arab neighbors—on Israel’s terms. For example, under the U.S.-brokered “Barrack paper” in Lebanon, the Lebanese Army would deploy to the south and receive international military aid to assert control. In theory, Israel would reciprocate by pulling back step-by-step from disputed border areas and offering economic incentives to Beirut. But the practical result would be that Israel no longer faces a potent irregular force at its border—only a regular Lebanese army that has never fired a shot at Israel.

Erdoğan’s Double Game: Rhetoric vs. Reality

No regional player illustrates the contrast between fiery rhetoric and pragmatic enablement better than Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He has long positioned himself as a champion of the Palestinian cause and a harsh critic of Israel – famously confronting Israel’s president in 2009 with a curt “One minute!” rebuke over Gaza. During Israel’s 2023 war in Gaza, Erdoğan slammed Israel’s actions as “genocide,” hosted mass pro-Palestine rallies, and even announced a boycott of Israeli goods and a ban on Israeli flights. This public posture has earned him plaudits on the Arab street. Yet behind the scenes, Erdoğan’s Turkey has remained deeply enmeshed with Israel – economically and strategically – essentially enabling the very state he decries.

Take the economic ties: Prior to the Gaza fallout, Turkey-Israel trade was booming, reaching nearly $10 billion annually. Even after Erdoğan’s government claimed to impose sanctions in 2024, Turkish companies quietly continued exporting materials ranging from raw materials and construction supplies to chemical products to Israel. When direct shipments to Israeli ports drew public ire, Turkey simply rerouted the trade through third countries. For example, exports to Greece suddenly jumped over 70% as many Turkish goods bound for Israel took an indirect path. Turkish officials insisted that “all trade [with Israel] had halted,” but investigative reports uncovered that Azerbaijani oil was still flowing via Turkey’s Ceyhan port to Israel’s Ashkelon refinery in late 2024. In fact, approximately 40% of Israel’s oil supplies come through the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline that runs across Turkey– a lifeline that was never truly shut off. Turkish activists opposing this trade pointed out the hypocrisy: Turkey was effectively fueling Israel’s military machinery even as Erdoğan thundered against Israeli aggression. When pressed, Turkish officials offered denials, but the data (including ship-tracking records) told a different story.

Another glaring example is steel and construction materials. Israel’s separation wall and settlement infrastructure have relied on imported steel – and Turkey has been a key supplier. During the supposed “embargo,” Turkish steel still found its way into Israeli projects, either through direct but opaque channels or via the Palestinian Authority (with goods nominally recorded as going to the West Bank, then transferred under Israeli control). As one expert noted, “In practice, [Erdoğan’s] Turkey have increased their economic relations with [Israel], supplying it with fuel, steel, and other necessities. One should not be deceived… by Turkey’s duplicitous and hypocritical policies.” Even the symbolic ban on Israeli flights using Turkish airspace turned out to be porous – flight trackers showed Israeli aircraft continuing to transit Turkey’s skies with Ankara’s tacit approval.

Erdoğan’s diplomatic and military posture toward Israel is equally two-faced. Publicly, he downgraded relations at times and expelled the Israeli ambassador during spats. Yet Turkey never truly left the Israeli camp. Security cooperation quietly endured; intelligence agencies reportedly maintained backchannels. In Syria, as noted, Turkish actions ended up aligning neatly with Israeli interests. By backing Islamist rebels who overthrew Assad, Turkey helped eliminate a staunch enemy of Israel’s without Ankara or Tel Aviv ever openly coordinating. Ankara always justified its interventions in Syria as operations against Kurdish “terrorists,” but in effect, Turkey had built a buffer in the north and bankrolled Sunni rebels—jihadists included—who have stood down against Israel and even tolerated Israeli occupation since the ousting of Assad last December. Indeed, Erdogan’s government celebrated HTS’s victory over Assad as a win for the Syrian people.

Even regarding the Syrian Kurds, where Turkey and Israel might seem at odds, there has been a tacit understanding. Israel initially expressed sympathy for Kurdish autonomy in Syria – an autonomous Kurdish region could have been a friendly buffer for Israel, and Israeli officials met with SDF representatives. Turkey, on the other hand, wanted the SDF dissolved. The compromise that emerged: the Kurds would integrate into the new Damascus regime with no army (satisfying Turkey’s insistence on no independent Kurdish state), and in return, they would get cultural rights and a limited role in Damascus. Indeed, when the integration deal was struck, Turkey’s foreign minister pointedly said the new Syrian administration should “grant the rights of Syrian Kurds”, indicating Turkey’s acceptance so long as its so-called concerns were met.

As previously explained, Ankara under Erdogan’s rule is unlikely to engage in military conflict with Israel, beyond rhetoric.. Erdoğan’s condemnations of Israel, however strident, stop at the point where they would translate into any material Turkish action against Israeli interests. In other words, Erdogan ultimately plays by the rules of the U.S.-Israeli order – even as he milks anti-Israel theatrics for domestic and Muslim-world consumption. By pressing to fold Rojava into Damascus and absorb the SDF into the army, Erdoğan and Tom Barrack advance a model that suits Israel’s long game: end militia autonomy, centralize coercion in the state, and, through future Israel-security arrangements, cap Syria with a de-weaponized military and no robust non-state actor.

In sum, Erdoğan exemplifies the “enemy in words, enabler in practice” pattern. His double game has helped create conditions highly favorable to Israel’s strategy: a weakened Syria, an isolated Hezbollah, and a Turkey that still provides Israel with resources despite loud arguments. Little wonder an Israeli-Turkish modus vivendi persists.

Tom Barrack: Washington’s Hand

Behind these regional maneuvers lies the guiding hand of the United States, often operating through envoys and deal-makers who connect the dots. One figure stand out: Tom Barrack – a billionaire businessman-turned-diplomat and confidant of former President Donald Trump – who has been a key behind-the-scenes actor in advancing the disarmament and reintegration agenda that aligns with U.S. and Israeli interests.

Tom Barrack, who in 2025 became both U.S. Ambassador to Turkey and Special Envoy for Syria. Barrack, a fluent deal-maker with deep ties to Gulf Arab elites, took on the ambitious task of finalizing the dual tracks of Lebanon’s Hezbollah disarmament and Syria’s SDF integration. By summer 2025, Barrack was shuttling between Middle Eastern capitals – he met Syrian interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa in Damascus, conferred with SDF commander Mazloum Abdi, and later traveled to Beirut. Barrack emerged as the public face of U.S. diplomacy on these files, giving interviews to the press about the progress. He openly stated that “the SDF must accept that Syria is one country, one army, one people” – firmly rejecting any Kurdish dreams of autonomy or federalism. He praised the new Syrian regime’s willingness to integrate former rebels and Kurds, saying Damascus had “done a great job” presenting options and that he hoped the SDF would “do it quickly” and respectfully. As a carrot, Barrack signaled U.S. “confidence” in the new Syrian military and even indicated that the U.S. was in “no hurry” to fully withdraw its remaining 1,300 troops, presumably to ensure the integration process held steady.

Followed Barrack’s interview with the Erbil-based Rudaw channel, in which he said the SDF’s only viable path is reconciliation with Damascus and argued that federalism is “not a workable model” for Syria, more than 35 political groups affiliated with the SDF have issued a joint statement condemning his comments, saying he overstepped his role as a mediator by rejecting federalism as a model for Syria.

In follow-up comments, he opened the door to asymmetric decentralization—short of full federalism—within a unitary Syria; even so, his plan leaves no room for an SDF with its own identity—only full absorption into the Syrian Arab Army.

In Lebanon, Barrack’s imprint is seen in what the New Arab termed the “Tom Barrack paper” – a comprehensive framework for Lebanese security reforms in tandem with a Lebanon-Israel accommodation offering Lebanon financial support and phased Israeli concessions if Beirut disarms Hezbollah. Barrack championed this roadmap, framing it as Lebanon’s “only lifeline” – a last chance to avoid collapse by embracing a U.S.-approved solution. When Lebanon’s cabinet took the U.S. advice and moved forward on the disarmament plan, Barrack was its loudest cheerleader internationally.

Recently, Barrack discussed the possibility of a “Sham Province“, which has stirred significant controversy in Lebanon and across the region. He warned that Lebanon could “go back to Bilad al-Sham”—the historical Greater Syria that includes present-day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan—unless Beirut takes action to curb Hezbollah’s arms and reconciles with Tel Aviv. On the surface, this suggests a scenario of Syrian reabsorption—a threat framed as renewed control by a neighboring Muslim country. However, this perspective primarily serves Israel’s strategic goals: it wouldn’t be Damascus “taking” Lebanon; it would be Israel taking it.

Together, Erdogan and Barrack’s behind-the-scenes work underscores that these “peace initiatives” were hardly spontaneous local ideas. They were nurtured, if not outright engineered, by Washington as part of a broader strategy to stabilize the region Israeli terms. The fact that Ambassador Barrack served as envoy for both Syria and Lebanon concurrently is telling – it suggests the U.S. sees these tracks as interlocking pieces of one puzzle. U.S. officials have essentially been cutting deals in Damascus, Ankara, and Beirut simultaneously: coaxing Turkey and the new Syrian leadership into an arrangement on the Kurds, convincing Lebanese leaders to confront Hezbollah, and quietly coordinating with Israel on what it will accept or concede in each case. At every step, the U.S. has leveraged its influence to align regional players with the grand strategy. This has included high-level moves like President Trump meeting Syria’s President al-Sharaa in May 2025 and agreeing to lift decades-old U.S. sanctions on Syria as a reward for the new regime’s cooperation. Washington even removed HTS from its terrorist list – a stunning turnaround driven by realpolitik. These actions make sense only in the context of the wider objective.

Looking Ahead: Policy Recommendations for Turkey

By removing autonomous armed groups without addressing the root causes that created them (Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands, disenfranchisement of Shia and Kurdish communities, etc.), these initiatives risk disarming the symptom while preserving the illness. Indeed, Hezbollah’s camp fears a trap: that once they’re disarmed, Israel will have free rein to dictate terms or even invade, as there would be zero guarantees Israel will stop its attacks if Hezbollah disarms. The Lebanese Army would be too weak alone, and the international community’s past failures to restrain Israel loom large in memory.

Similarly in Syria, Kurds fear that “integration” could leave them exposed: will Jihadist Arab generals in Damascus honor pledges on language, local governance, and security—or walk them back once U.S. troops depart? And if Israel turns its attention to Kurdish-run areas, as Öcalan warned from İmralı, what then?

It is important to note that immediately after Assad was ousted in December 2024, Israel expanded its military strikes. They targeted weapons depots not only in areas controlled by Damascus but also in Kurdish-controlled zones. Israel could have allowed the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to take these weapons as gifts, but it chose not to. Were they concerned that these weapons could end up in the hands of Damascus once the SDF was absorbed?

These “peace” initiatives are serving a grand strategy – one meticulously planned in Tel Aviv and Washington, and facilitated by regional actors like Erdoğan, may indeed remove immediate flashpoints of violence and usher in short-term stability, but it’s a stability underpinned by the dominance of one side. Peace can take two forms: it can be the fruitful result of justice and mutual respect, or it can be the peace of a chessboard, where every piece is in its prescribed place after the game’s outcome is decided. We fear this ‘peace’ is the latter. Erdoğan’s Turkey and Barrack’s diplomacy have helped “checkmate” the last opposition on that board, clearing the way for what could be a Pax Israela – an Israel-centric peace.

Against his background, If Ankara is serious about regional stability—and about blocking outside actors from instrumentalizing Syria’s fault lines—it should champion a settlement that recognizes Syrian Kurds’ identity and role inside Syria’s state structure. That means backing asymmetric decentralization—short of full federalism—with constitutional guarantees for Kurdish language, education, and cultural rights; empowered local or municipal councils; and distinct Kurdish units (or as an army) fully subordinated within the Syrian Arab Army’s command. Such a model best serves Turkey’s own national interest.

Politically, this approach would help Turkey win hearts and minds—not only among Syrian Kurds but also among other Kurdish communities and Arab populations across Syria and the wider Middle East. For Kurds, it signals that Ankara supports dignity, representation, and local agency inside a unitary Syria rather than perpetual limbo. For Syrian and regional Arabs, it demonstrates that Turkey prefers inclusive state rebuilding over zero-sum experiments that produce endless fragmentation. The payoff is a reputational shift: Turkey becomes the credible broker of an inclusive order, rather than a stakeholder seen as vetoing Kurdish aspirations or enabling endless conflict.

Economically and diplomatically, the dividends compound. A rights-anchored, decentralized Syria—policed by integrated local units under national command—creates conditions for safe refugee returns, opens cross-border trade corridors from Gaziantep–Kilis to Qamishli–Hasakah, and enables joint reconstruction and energy-transit projects. It also strengthens Ankara’s hand with Baghdad and Erbil by modeling a rights-respecting template that reduces friction across Kurdish geographies and encourages rules-based connectivity rather than patron-client dependencies.

Even if Ankara enjoys a tactical thaw with Damascus today, the balance could tilt quickly as other regional actors—Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Gulf capital more broadly—deepen their footprint in Syria’s reconstruction, logistics, and, inevitably, its political orientation. Chequebook influence could erode Turkey’s current advantage and status. In short, a Rojava integrated into Damascus—with separate, identifiable Kurdish units (or as an army) retained but subordinated under Syrian Arab Army command—gives Turkey a durable buffer and bargaining chip as outside actors ramp up economic and political penetration.

The example has been in plain sight for decades: Which serves Turkey’s interests better—an Iraq of rigid Ba’athist centralism, a unitary state closely tied to Iran, or the current federal system where Kurds govern themselves?

By: GEOPOLIST – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics