Former U.S. Special Representative for Syria James Jeffrey has pushed back against claims that Washington’s shifting posture in Syria amounts to a “betrayal” of the Kurds, arguing that U.S. officials consistently framed their partnership with Kurdish-led forces as limited to defeating ISIS and never as an open-ended security guarantee. Speaking in Washington in remarks reported as having been given to Voice of America (VOA), Jeffrey said the relationship was “temporary” and “tactical,” rooted in shared interests against ISIS rather than a promise to defend Kurdish forces against any and all adversaries or to back a permanent Kurdish region.

Jeffrey’s comments land amid renewed controversy over how the U.S. handled the endgame of Syria’s Kurdish-run autonomous zone. A recent Reuters investigation described how Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s forces moved to dismantle Kurdish-held governance structures in the northeast while U.S. messaging increasingly emphasized that Washington’s priority was a unified Syrian state and integration of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) into national frameworks, fueling Kurdish accusations of abandonment.

In the VOA-linked remarks, Jeffrey also tied Washington’s preferred end state to U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254, which endorses a Syrian-led political process while reaffirming Syria’s sovereignty and territorial integrity—language frequently invoked to argue against partition or externally imposed statelets.

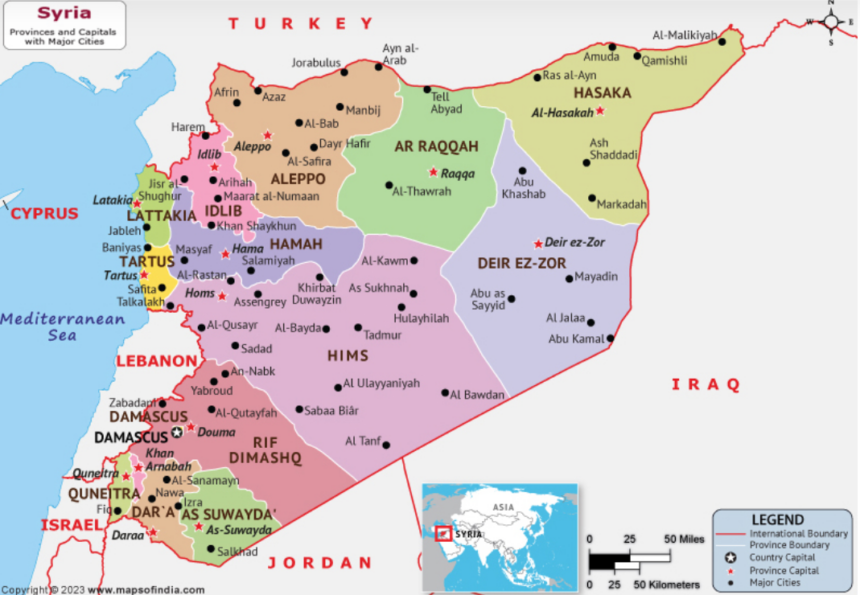

Where Jeffrey’s intervention becomes especially notable is in his governance prescription for postwar Syria. He argues that Syria should move toward a provincial or “state/governorate” model that devolves meaningful authority to local administrations—an approach he likened to elements of Iraq’s system—while explicitly rejecting the idea that Syria should replicate Iraq’s Kurdish-region model. In this framing, Kurdish forces would be integrated into the Syrian army, while Kurdish-majority areas would retain significant local administrative powers, including public-security arrangements at the local level, without formalizing an ethnically defined federal region.

That general template closely echoes an earlier proposal published by News About Turkey in May 2025, which argued for “decentralization without division” and urged a Syria-wide municipal governance reform inspired by Turkey’s Law No. 6360. That NAT commentary presented decentralization as a countrywide administrative design—rather than an ethno-federal carve-out—intended to preserve territorial unity while granting communities real authority over local governance, including culturally sensitive areas such as education and local administration, and practical domains such as service delivery and public order.

The NAT proposal anchored its model in Turkey’s 2012 Law No. 6360, which expanded the metropolitan municipality system to provinces above a population threshold and reshaped the relationship between the center and the periphery through technocratic municipal restructuring rather than constitutional federalism. In describing the law’s broader mechanics, comparative governance profiles note that the 2012 reform (implemented with the 2014 local-election cycle) extended the metropolitan municipality regime to all provinces above 750,000 inhabitants and altered the architecture of provincial administration in those areas. The NAT piece argued that a Syria-specific analogue—built around standardized municipal authorities, budgetary competence, and local administrative capacity across the country—could offer Kurds, Druze, and other communities meaningful self-management while avoiding a formal ethnic federal map that regional states, including Turkey, have repeatedly rejected.

The overlap between Jeffrey’s remarks and the earlier NAT framework is less about identical institutional blueprints than about shared political geometry: both approaches treat decentralization as a function of administrative design within a unitary state, not as a step toward secession or a rigid ethno-territorial settlement. Both also converge on the idea that the durable pathway for Kurdish areas runs through integration into national structures paired with robust local governance powers—an argument that sits uneasily with maximalist autonomy slogans, but also with hardline centralization.

At the same time, the politics around any “autonomy model” remain volatile. Turkey, for example, has publicly opposed decentralization rhetoric in Syria while emphasizing that armed force should be centralized under state authority—positions that complicate how far any devolved governance arrangement can go in practice. And on the ground, the rapid collapse of the SDF’s autonomous enclave, and the dispute over what assurances the U.S. did or did not give, continue to shape how Kurdish actors—and their critics—interpret Jeffrey’s insistence that there was never a promise of protection beyond the ISIS fight.

By: GEOPOLIST-Istanbul Center for Geopolitics