Summary by Geopolist | Istanbul Center for Geopolitics:

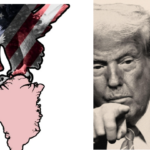

The article discusses the geopolitical situation in Transnistria, a breakaway region in Moldova, highlighting the limits of the domino theory in international relations. Key points include:

- Vadim Krasnoselski’s Congress: On February 28, Transnistrian leader Vadim Krasnoselski held a congress to discuss Moldova’s customs duties on Transnistrian businesses, calling for Russian protection. This sparked fears of Transnistria integrating into Russia and becoming a new frontline in the Russia-Ukraine war.

- Domestic Reactions: Valeriu Pașa, president of Watchdog, suggested the congress was a maneuver to influence public opinion. Oleg Serebrian, Moldova’s vice-prime minister, indicated that Transnistria’s leadership, business environment, and population do not support the war, aiming to balance relations with Moscow, Kiev, and Chisinau.

- Putin’s Ommission: Russian President Vladimir Putin did not mention Transnistria in his State of the Union address, suggesting no imminent escalation.

- Domino Theory’s Limitations: The situation highlights the limitations of the domino theory, which suggests that the fall of one country to a particular influence leads to a chain reaction. Transnistria’s situation shows the need for a nuanced understanding, considering internal factors, bilateral and multilateral relations, and the strength of political, economic, and social institutions.

- Conflict Fundamentals: The seven-point resolution adopted by Tiraspol aims to empower the Kremlin to escalate against Moldova. However, Russia lacks territorial continuity with Transnistria and is not in a position to control the border or support a war effort there. The conflict has remained frozen for nearly 30 years, with neither side wanting an armed confrontation.

- European Assistance: Moldova may need European assistance to face potential Russian destabilization. The situation could change if Russia makes significant progress on Ukraine’s southern front, near Odessa, which is close to Tiraspol.

In summary, the Transnistria case illustrates the complexity of international relations and the shortcomings of the domino theory, requiring a more detailed and context-specific analysis of geopolitical dynamics.

For more details, read the full article here below.

On 28 February, the leader of Moldova’s breakaway region of Transnistria, Vadim Krasnoselski, held the Seventh Congress of Deputies to discuss the implications of Moldova’s latest customs duties on Transnistrian businesses. His calls for Russia’s protection in response to Moldova’s “economic strangulation” sparked fear in many international observers of an imminent integration of the region into Russia, and even of a new frontline in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Far from the international uproar, reactions on the domestic front were much more measured. Valeriu Pașa, president of one of the main think tanks in Chisinau, Watchdog, suggested that this Congress appeared more like a manoeuvre aimed at influencing public opinion. Meanwhile, in March Modolva’s vice-prime minister tasked with the mission of reintegrating Transnistria, Oleg Serebrian, sought to allay anxieties:

“Tiraspol is attempting to avoid positioning itself in any way, balancing itself acrobatically between Moscow, Kiev and Chisinau. What we can say with certainty is that Tiraspol does not want to be involved in this conflict. In particular the administration. The business environment, as well as the population, definitely does not favour war. I have not met anyone on the left bank who says they support the war,”

Undeniably, this perception was reinforced by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s omission of Transnistria in his State of the Union on the next day.

This contrast between fears of imminent escalation and relative calm on the ground raises crucial questions about our understanding and interpretation of the events at play. It highlights the limitations of the domino theory metaphor, often used to explain and anticipate conflict dynamics, but which can lead to analytical errors and misguided perspectives, especially in the context of the war in Ukraine.

What is the domino theory’s purpose?

Since February 2022, the hypothesis of the Ukrainian war’s expansion has resurfaced regularly: if Ukraine falls, other countries will inevitably become targets for Russia. None seems more likely than Moldova, a neighbouring neutral country whose president, Maia Sandu, has openly defied Russia since the beginning of the war in Ukraine.

In essence, the domino theory combines in its analysis the idea of contagion (the first fall triggering a chain reaction due to geographical proximity), a belief in regional stability (the fall of a key country can disrupt regional balance), and the perception of a particular influence (the spread of influence can attract supporters in other countries by offering an attractive alternative to existing systems). In geopolitical terms, the domino theory suggests that if a country or region falls under the influence of an ideology or regime, it could trigger a series of similar falls in neighbouring countries, much like dominoes falling one after another when pushed.

This approach, which drove US president Harry Truman (presidential term 1945-1953) to support governments in Greece and Turkey following the Second World War, was explicitly formulated in April 1954 by President Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961) during a 1954 press conference commenting on the developments of the Indochina War:

“Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the ‘falling domino’ principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.”

This perspective profoundly influenced US strategic thinking during the Cold War, undergoing several iterations. Recently, among others, Brandon Temple, a special warfare officer in the Air Force serving as a legislative liaison to the House of Representatives, and researcher Mark Episkopos have observed and lamented the return of these old strategic frameworks during the war in Ukraine.

When it comes to Transnistria, this pattern seems straightforward enough: the summoning of “deputies at all levels” mirrors the sequence observed at the start of the 2014 war, whereby the annexation of Crimea gave way to the declarations of independence of Donetsk and Luhansk. Russian president Vladimir Putin notably justified the invasion on the grounds of protecting the two latter pseudo-states.

Why doesn’t it apply to Transnistria?

If the Congress proceeded as planned, it’s obvious that the Transnistrian domino didn’t fall on this occasion. Therefore, it is worth pausing to consider the limits of this metaphor and observable developments in the Transnistrian conflict.

Indeed, since the early 1960s, domino theory has faced criticism for overlooking various parameters; metaphors shape our perceptions, reinforce biases, and sometimes mask complexity, thereby exposing their limitations. In his famous New York Times magazine article in April 1965, Hans Morgenthau, one of the founders of the classical realist school, opposed increasing US involvement in Vietnam for this reason.

Main critiques of this theory include insufficient consideration of internal factors, local political, economic, and social dynamics; the oversight that bilateral and multilateral relations between countries can play a crucial role in impacting events and perception; recognition that a country’s political, economic, and social institutions’ strength can determine its ability to resist external pressures and maintain stability; and that external actors’ intervention and influence can significantly impact event evolution. Finally, cultural and historical differences between countries can influence how ideas and events are perceived and interpreted.

Concretely, one must revert to the fundamentals of the specific conflict. Indeed, one might argue that the seven-point resolution adopted by Tiraspol in late February 2024 aims to empower the Kremlin to escalate against Moldova. It is precisely to combat such hybrid threats from Russia that the European Union launched a civilian partnership mission in the country in 2023. Today, there are numerous ways Moscow can influence political dynamics in Chisinau, especially during this presidential election year.

Despite similarities with the resumption of the Georgia (August 2008) and Ukraine (since February 2022) wars, there is one major difference here, namely, the absence of territorial continuity between Russia and Transnistria. The Russian Federation is neither in a position to control the border between Transnistria and Ukraine, nor to send arms to support a war effort, nor to take over from the troops present there (1,500 peacekeepers plus a few thousand local forces), whose military potential is otherwise limited. Neither Transnistria nor Moldova, which have not faced each other militarily for nearly 30 years, envisions an armed exit from this conflict, if only because neither wants their territories to become battlefields comparable to those of the Donbass.

In short, while Moldova might need European assistance more than ever to face up to threats of Russian destabilisation, we can’t be sure the resumption of the Transnistrian conflict is the most imminent risk. However, the situation would of course change radically if Russia were to make significant progress on Ukraine’s southern front, in the Odessa region; the city is only, after all, a hundred kilometres from Tiraspol.

By: Florent Parmentier

Source: The Conversation