Turkey’s impending leadership transition is as much a geopolitical pivot as a domestic power shift. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s long rule (over two decades) has centralized authority in him and his inner circle, raising urgent questions about who follows him. Speculation has focused on his own family – notably his son Bilal Erdoğan – and on powerful lieutenants like Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan. But As News About Turkey (NAT) noted in recent months, the only realistic non-family candidate is presidential aide-turned-intelligence chief İbrahim Kalın.

.This view captures Kalın’s unique status as a seasoned insider yet outsider to the Erdoğan family dynasty. It also underscores the symbolic appeal of Kalın’s candidature: he is seen as the sole Erdoğan lieutenant with the academic stature and diplomatic gravitas to carry Turkey into a new era.

Kalın’s combination of scholarship, statesmanship, and security credentials makes him uniquely acceptable to both Turkey’s establishment and its external partners, ranging from Arab capitals to Western allies. In contrast, Bilal Erdoğan lacks governing legitimacy and intellectual depth, while Hakan Fidan faces strategic and intellectual constraints. We begin by surveying how each contender is perceived by key international actors. We then profile Bilal Erdoğan and Hakan Fidan in depth, before making the case for Kalın. Finally, we assess the broader regional stakes of Turkey’s succession – underscoring why a dynastic transfer could derail the country’s strategic course.

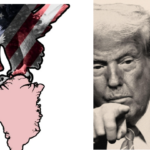

Geopolitical Shift: The U.S.–Gulf “Sunni Axis”

Any serious discussion of succession in Turkey must begin not with personalities, but with the geopolitical order the United States is actively trying to consolidate across the Middle East and in Central Asia. Since late 2024, Washington has moved decisively away from ad hoc crisis management towards a more coherent—though risky—regional architecture. This approach focuses on consolidating Sunni and Salafi groups along with Turkish and Arab nationalism, selectively tolerating Salafi-adjacent actors, and rolling back Iranian and Russian influence, with the eventual goal of countering Chinese influence in these regions.

This broader regional context has lately thrust Turkey onto center stage as part of a new “Sunni axis” strategy backed by the United States and Gulf states. Washington and its Sunni partners have quietly fostered an alliance spanning Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey and like-minded factions to roll back Iranian influence. Syria has become the test case. In late 2024, the Assad regime crumbled under a rebel coalition led by Turkey-backed Salafi-jihadist forces (most notably Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham under Ahmed al-Sharaa). Turkey and Saudi Arabia swiftly embraced the new Islamist-led interim government in Damascus despite its hardline character, viewing it as a Sunni counterweight to Iran. Importantly, U.S. officials tacitly accepted this outcome: they intervened neither militarily nor diplomatically to protect the U.S.-allied Kurdish-led SDF from Turkish pressure.

This “Salafi consolidation” – the fusion of Islamist movements and state power – is extending beyond Syria. As we have recently argued, Iraq may be next in line, with Sunni Arab forces backed by Washington and Ankara seeking to erode Iran-backed Shia dominance. Kurdish fears are rising. We have also noted that a revived Sunni-dominated Baghdad “backed by Turkey and the Gulf” could move to shrink the KRG’s autonomy – for example, asserting federal control over disputed Kurdish regions and oil fields. A U.S.-supported Sunni coalition is reshaping the geopolitical landscape from Idlib to Baghdad to East Turkistan. Its momentum relies on Turkey’s cooperation, serving as the northern anchor of a Turkic Belt that stretches from the “Adriatic Sea to the Great Wall of China”.

Kalın’s Role in the New Order

İbrahim Kalın’s credentials span scholarship, religion and diplomacy. He earned a BA in history from Istanbul University and went on to earn a master’s in Islamic philosophy in Malaysia and a PhD in Islamic studies at George Washington University (2002) under the prominent thinker Seyyed Hossein Nasr—an Iranian philosopher who went into exile after the 1979 revolution and is also the father of political scientist Vali Nasr. Kalın’s engagement with Nasr’s thought is not just biographical: his official profile notes that he authored a chapter on Nasr’s philosophy of science, signalling a sustained, serious investment in that intellectual lineage.

In this regard, Kalın’s background as an Islamic studies scholar and intellectual distinguishes him from other power brokers. He has taught at Istanbul Technical University, Sabancı University, and even been rector of Istanbul Şehir University. He held visiting fellowships at Harvard, Oxford and Georgetown universities. All this underscores Kalın’s fluency in global academic and diplomatic milieus. Indeed, he speaks English, Arabic, Persian and French fluently, an extraordinary linguistic repertoire that lets him communicate easily with Western, Arab and broader Muslim interlocutors. The Washington-based Foreign Policy magazine even named him a 2019 “Global Thinker,” recognizing his international standing. In public, Kalın is seen as calm, articulate, and thoughtful – a polyglot scholar-politician rather than a raw partisan operative.

In 2005 Kalın founded the SETA think tank in Ankara and directed it until 2009. Later he served in Erdoğan’s administration as foreign policy advisor and in communications roles. In December 2014 Kalın was named the first official Presidential Spokesperson, a post he held until June 2023. In June 2023 President Erdoğan tapped him to lead the National Intelligence Organization (MİT), a role confirming Kalın’s centrality in Turkey’s strategic affairs.

Since then, even much before, as a top security advisor, in Turkey’s contribution to the emerging “Sunni axis,” İbrahim Kalın has not been a background operator—he has been visibly staged as a front-line emissary. Immediately after Assad’s fall, Ankara dispatched senior delegations to Damascus to engage the HTS-brokered transitional leadership. Most symbolically, it was Kalın—rather than Hakan Fidan—whose visit to Damascus included a high-profile appearance at the Umayyad Mosque, a carefully choreographed gesture that carried political meaning beyond protocol. In a region where symbolism is strategy, the choice of messenger matters: Kalın’s prominent role signaled not only access, but Erdoğan’s intent to present him as a trusted interlocutor for the new Islamist-leaning order in Syria—a figure who can speak to religious legitimacy while remaining legible to international audiences.

In one of the most striking moments from that trip, footage circulated showing Syria’s new leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, personally driving Kalın through Damascus in a black sedan to pray at the Umayyad Mosque. Since the earliest stages of the Syrian civil war, Turkey’s ruling elites—Erdoğan included—have repeatedly treated the Umayyad Mosque as a rhetorical symbol of victory, often framing “praying there” as the promised endpoint of the war and a shorthand for a post-Assad Syria aligned with Ankara’s interests.

That positioning strengthens Kalın’s credibility on the two files that will define Ankara’s post-SDF environment: Syria’s reconstruction and the Kurdish question. His profile is unusually “dual-use” in diplomatic terms. On the one hand, his Islamic intellectual background and conservative cultural fluency can reassure Gulf partners who often distrust hard secular-nationalist styles. On the other hand, his Western academic formation, multilingual competence, and long experience as Erdoğan’s chief foreign-policy voice make him easier to “process” in Washington and European capitals than a purely security-bureaucratic figure.

Crucially, Kalın embodies the hybrid profile the U.S.–Gulf alignment increasingly prefers in Ankara: religiously authentic enough to interface with the region’s Sunni reconfiguration, yet institutionally polished enough to preserve Turkey’s NATO-facing credibility. Western governments may remain uneasy about Ankara’s ideological drift and its selective toleration of Islamist actors, but Kalın’s technocratic tone and “statesman-intellectual” persona can mute those anxieties. His participation in the reconciliation of Sunnis and Kurds in Syria (through the “Democratic Spring” proposals, for instance) shows a pragmatic streak. In effect, Kalın can help Ankara navigate the delicate balance between Turkey’s nationalist-Islamist currents and its need to maintain ties with NATO and Gulf allies.

He is typically read less as a conspiratorial hard-liner and more as a disciplined strategist who can translate Islamist-coded politics into the language of stability, counterterror coordination, and state reconstruction. In that sense, his visibility in Damascus was not incidental. It was a signal: if Turkey’s next phase is about consolidating a Sunni-aligned regional order while avoiding a rupture with the West, Kalın is the one figure designed to sell that balance—externally and internally—without making Ankara look hostage to either dynasty or shadow-state security politics.

Contenders and Their Liabilities

Turkish succession talk also revolves around Erdoğan’s son – Bilal Erdoğan – and his former spymaster, Hakan Fidan.. Bilal’s profile is real, but it is institutional-by-proxy rather than governmental: he has built visibility through a network of youth, education, and values-oriented foundations that overlap with the AKP-era patronage ecosystem, including TÜGVA and related structures at home and abroad. In recent years, that visibility has also taken a more overtly political form. Bilal has appeared as a high-profile voice at mass mobilizations—particularly pro-Palestinian rallies—where he is treated less as a policymaker than as a symbolic carrier of the regime’s ideological narrative and a recognizable surname for base consolidation.

That is precisely where his liabilities begin. Unlike institutional successors who can point to cabinet responsibility, parliamentary experience, or a track record of crisis management, Bilal has never held elected office or a senior executive post within the state. His public legitimacy therefore rests mainly on dynastic proximity and movement infrastructure—dorms, scholarships, youth networks, and foundation-linked social capital—rather than performance in governance.

Bilal also carries reputational baggage that can re-enter the international conversation at the worst possible moment—during a transition. He was named in the 2013-era corruption allegations and subsequent legal disputes that became a defining rupture in Turkish politics; even when cases are closed or contested.

None of this means Bilal is politically irrelevant. On the contrary, his value—if the regime pursued him—would be as a mobilizational brand and as a guarantor of family continuity for a loyalty-tested conservative youth constituency. But that is exactly why many observers see him as a high-risk succession vehicle: he may consolidate the base while simultaneously widening elite hesitation at home.

Hakan Fidan, by contrast, is a seasoned insider with decades of intelligence and security experience. He ran the intelligence service and now serves as foreign minister—roles that have made him one of the most consequential power brokers in Ankara. But his external brand is more polarizing.

A key constraint is perception, especially in Western adn Israeli security circles, where suspicion about Ankara’s Iran channel has periodically attached itself to Fidan personally. The roots of today’s suspicions surrounding Hakan Fidan can be traced back to the Selam–Tevhid investigation, a sprawling counterintelligence case in the early 2010s centered on alleged Iranian networks operating in Turkey. Although the investigation was later folded into the broader post-2016 purge narrative and recast as a Gülenist plot, it left a lasting imprint in Western and Israeli intelligence circles: the perception that Turkey’s intelligence leadership was unusually tolerant of Iranian operational space. It was in this climate that Israeli intelligence officers were reported to have joked to CIA counterparts that Fidan was “the MOIS station chief in Ankara”—a pointed reference to Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security. The phrase mattered not because it was a proven fact, but because it crystallized a perception: that Fidan was a figure comfortable operating beyond a strictly NATO-centric lane. Over time, this image aligned him—fairly or not—with a broader Eurasianist strategic current that treats Iran, Russia, and increasingly China not as ideological allies but as counterweights to Western pressure.

Beyond questions of ideology and power networks, intellectual depth and communicative reach remain critical differentiators among the succession contenders. On this axis, neither Bilal Erdoğan nor Hakan Fidan compares favorably with İbrahim Kalın. Bilal Erdoğan’s public role has been almost entirely domestic and symbolic; he has not demonstrated sustained engagement with complex policy debates, nor the linguistic or conceptual tools required for high-level international representation. Fidan, despite his extensive operational experience, presents a different but related limitation. Since assuming the foreign minister portfolio nearly three years ago, he has remained largely absent from English-language policy forums and international media. Notably, his first substantive interview in English as foreign minister came only recently, in a conversation with Al Jazeera—a striking contrast with peers who routinely operate in multilingual diplomatic environments.

This matters because, in the current geopolitical climate, leadership credibility is increasingly tested not only through back-channel leverage but also through public-facing diplomacy: interviews, multilateral panels, and narrative framing across global platforms.

Conclusion: A Successor Shaped by Geopolitics

Turkey’s looming succession question cannot be divorced from shifting regional power alignments. The new U.S.–Gulf-backed order in the Middle East – embracing Sunni/Salafi partners against Iran, Russia and eventually China – means Ankara’s future leader must fit into that scheme. İbrahim Kalın, with his blend of Islamist legitimacy and Western polish, is arguably the figure best calibrated for such a role. In Kalın, allies see a politician who can continue pro-Sunni axis policies (as evidenced by his role in Syria) while maintaining bridges with Europe and the US. In a “post-Erdoğan” era, the West and Gulf capitals would likely prefer a leader like Kalın over a family member with zero statecraft or a security chief with alleged Iranian ties and limited intellectual depth and linguistic skills.

By: GEOPOLIST-Istanbul Center for Geopolitics