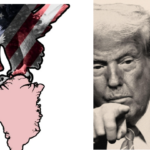

Recently, an alluring idea has gained currency, especially after the US operation on the first days of this year in Venezuela: the world could be drifting toward a tripartite great-power condominium, a tacit arrangement where the United States, China, and Russia carve the globe into exclusive spheres of influence. In this vision, Washington would preside over the Western Hemisphere, Beijing over Asia, and Moscow over its European hinterland – a neat division meant to preserve peace through a balance of giants. Proponents of this concept argue that clear demarcation of influence zones among the three top powers could prevent direct conflicts, akin to an updated Concert of Powers. It’s a narrative of an emerging order in which great-power rivalry gives way to pragmatic power-sharing – a de facto Yalta 2.0.

For those hoping or predicting that the United States, China, and Russia might settle into a stable tripolar world of partitioned spheres, recent American behaviour tells a different story. Rather than acquiescing to a de facto power-sharing arrangement, Washington continues to act as if primacy is still up for grabs. In theory, a Concert of Great Powers dividing influence sounds orderly; in practice, U.S. policy across multiple regions has been anything but restrained. From the Middle East to the Caucasus and deep into Eurasia, the United States is actively leveraging its military, alliances, and networks to shape outcomes unilaterally – often at the direct expense of Russian and Chinese ambitions. We examine five arenas where America’s conduct contradicts the notion of a neat U.S.–China–Russia condominium. Far from embracing a partitioned global order, Washington seems determined to extend its post-Cold War primacy through regional leverage and coalition-building. The result is not a stable balance of separate hegemonies, but a complex and friction-filled contest among major powers.

Unilateral U.S. Power Plays in the Middle East

Nowhere is the United States’ refusal to cede influence more evident than in the Middle East. Even as talk of great-power “spheres of influence” circulates, the U.S. maintains a robust, often unilateral military posture across the region. In fact, American troop levels in the broader Middle East climbed from roughly 34,000 to nearly 50,000 by late 2024 – a buildup unseen since the height of the first Trump administration. This surge was largely under the radar, but it involved highly visible moves: Washington deployed no fewer than three aircraft carrier strike groups near Yemen as part of a mission to secure maritime transit in the Red Sea. U.S. warships and air power, under the banner of Operation Prosperity Guardian, patrolled critical waterways after Houthi rebels (aligned with Iran) attacked oil tankers and cargo ships in late 2023. In parallel, the Pentagon forward-deployed B-2 stealth bombers to the Indian Ocean base at Diego Garcia – one of the largest such deployments on record – explicitly to project power over the Strait of Hormuz and deter Iran. These actions amount to Washington unilaterally asserting its role as guarantor of Middle Eastern shipping lanes, reinforcing a decades-old commitment to defend global energy routes. U.S. military planning has long anticipated scenarios like Iran attempting to close Hormuz or seize Gulf oil infrastructure, and America continues to prepare for – and preempt – such threats. Far from stepping back to let regional powers police their own neighborhoods, the United States still behaves as the indispensable security provider for the oil-rich Gulf and beyond. This muscular posture belies any notion that Washington will quietly accept a limited sphere in the Americas while yielding the Middle East to others. On the contrary, through unilateral force deployments and “free navigation” operations, the U.S. signals it will personally safeguard the flow of energy that underpins the world economy – spheres-of-influence be damned.

Israel’s Security Depends on American Primacy

If a truly shared global hegemony were to take root, one country’s position would be fundamentally imperiled: Israel. The strategic centrality of Israel in U.S. planning cannot be overstated – and it illuminates why Washington finds a power-sharing world order untenable. Israel’s survival and military dominance in its region are structurally predicated on continued U.S. primacy. Washington doesn’t just support Israel as a partner; it underwrites Israel’s qualitative military edge over any combination of regional adversaries. Annual American military aid of roughly $3.8 billion, alongside unfailing U.S. diplomatic protection (for example, at the United Nations), form the backbone of Israel’s power. This overwhelming support has enabled Israel to field cutting-edge weaponry and missile defenses that no rival can match – an advantage Israel could not sustain if the U.S. were merely one great power among peers. Indeed, Israel remains heavily dependent on Western backing. As we noted previously, if U.S. (and European) support were to diminish due to shifting politics, Israel would lose its ability to maintain its current position and very existence. American strategists openly acknowledge this reality. The U.S. has long sought to ensure Israel’s qualitative military edge (QME) by supplying top-tier technology and co-developing defense systems. Crucially, U.S. dominance deters other big powers from overtly arming or backing Israel’s foes. A world of stable spheres, where Russia or China exercise equal sway in the Middle East, would erode that deterrence. Moscow and Beijing have, in fact, tried to undermine Israel’s strategic position by courting its adversaries. Only a globally preeminent U.S. can credibly guarantee Israel’s security against such great-power meddling. Thus, America’s unconditional backing of Israel stands as a stark contradiction to theories of a U.S.–China–Russia power-sharing détente – it’s a non-negotiable commitment that effectively locks the U.S. into a dominant global role.

Undercutting Russia in the Caucasus

Another arena where U.S. behavior clashes with the idea of neat spheres of influence is the South Caucasus. Traditionally, this region fell squarely within Moscow’s post-Soviet “backyard” of influence. Yet recent U.S. diplomatic maneuvers in Armenia and Azerbaijan have upended that assumption, directly challenging Russia’s role as regional arbiter. The flashpoint is a project known as TRIPP – the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity. Brokered by Washington in 2025, TRIPP is a transport corridor that would connect Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave through Armenian territory. In essence, it mirrors the long-proposed “Zangezur corridor” sought by Baku and Ankara, except with one crucial twist: the United States would lease, develop, and manage the Armenian section of the route for 99 years. This plan – unveiled after a White House summit with Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s leaders – represents a dramatic insertion of U.S. influence into the Caucasus transit geography. The impact on Russian clout is unmistakable. Under the Moscow-brokered ceasefire that ended the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, any such corridor was to be under Russian control (with Russian border guards securing transit). Washington’s TRIPP deal explicitly supplants that arrangement, pushing Russia to the sidelines. In strategic terms, the U.S. move in Armenia-Azerbaijan is a bold bid to disrupt Russia’s traditional influence and secure a foothold on the cusp of both the Russian and Iranian borders. It signals that Washington is willing to reach into the heart of Eurasia’s old “buffer zones” to advance an order on its terms. Such behavior is fundamentally at odds with the notion of Washington gracefully accepting a Eurasian sphere under Moscow’s dominion. Instead, the U.S. is carving out influence where it can – even in Russia’s shadow – to shape a new regional order more favorable to itself and its allies.

A “Turkic Belt” to Box In Russia and China

In tandem with its Caucasus foray, the United States appears to be encouraging the rise of a transnational Turkic alliance as a geopolitical counterweight across Eurasia. This centers on the burgeoning Organization of Turkic States (OTS) – a bloc comprising Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan, with Turkmenistan as an observer. What began over a decade ago as a cultural cooperation council has recently transformed from a cultural forum into a dynamic geopolitical bloc under Turkey’s assertive leadership. With Russia’s war in Ukraine weakening Moscow’s grip, the OTS is consolidating political, economic, and security cooperation among Turkic-speaking nations, creating an emerging alternative to Moscow’s dominance in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. In plainer terms, a new “Caspian–Caucasus axis” led by Ankara and Baku is operating increasingly “outside Russia’s sphere of influence.”

Washington has taken note – and, if anything, is subtly abetting this trend. In late 2025, the OTS Secretary-General paid an unusually quiet but geopolitically significant visit to Washington, meeting U.S. State Department and congressional officials. The timing was no coincidence: it followed President Trump’s summit with Central Asian leaders at the White House and the U.S.-brokered Armenia–Azerbaijan breakthrough. These moves underscore the growing strategic relevance of the Turkic bloc and Washington’s interest in closer ties. The appeal of the OTS to U.S. strategists is clear. Spanning from Anatolia to the doorstep of western China, Turkic states sit atop resource wealth, key trade corridors, and a combined population of over 150 million. Perhaps most importantly, the bloc offers an additional strategic pull across Eurasia at a time when the landscape is otherwise dominated by Russian and Chinese influence. In fact, the OTS’s flagship initiative – the so-called Middle Corridor linking Europe to Asia via Turkey and the Caspian Sea – explicitly bypasses Russia. It creates alternative east–west routes that diminish Moscow’s leverage and even challenge China’s Belt and Road arteries. Washington has every reason to quietly cheer this on. By boosting connectivity among Turkic partners (logistically and culturally), the U.S. erodes the infrastructure monopolies and Eurasian integration schemes that Russia and China bank on. An empowered Turkic alliance also poses an implicit check on Beijing’s interests. Thus, Beijing views the OTS with growing concern, partly because a pan-Turkic revival could embolden Turkic Muslim populations in China’s Xinjiang region. (Xinjiang’s native Uyghurs are ethnically Turkic, and China’s deepest fear. A revitalized Turkic identity might undermine Beijing’s assimilation efforts in that sensitive province. Even Iran – ostensibly a U.S. adversary – finds itself uncomfortably encircled by the Turkic resurgence. Northern Iran is home to a large Azerbaijani Turkic community, making up an estimated one-quarter of Iran’s population (by some counts) concentrated along the border. The vision of a cross-border “Turkic belt” thus touches Iran’s domestic fabric as well. It’s not lost on Tehran that a strong Azerbaijan–Turkey axis, backed by Western powers, could inspire irredentist sentiment among Iran’s Azeri (Turkish) minority. In effect, the Turkic integration project complements U.S. containment of both Russia and Iran – even if American officials rarely say so out loud. This is why voices in Washington have begun urging elevating ties with the Turkic bloc. Closer U.S.-OTS cooperation makes strategic sense as it would put America’s presence at the heart of Eurasia and reinforce a regional order not centered on Moscow or Beijing. The Biden and Trump administrations alike have engaged more with Central Asia and courted Turkey’s role, suggesting a bipartisan recognition of the opportunity.

However, Iran’s role as Israel’s “useful foil” no longer appears to generate the same strategic value it once did: in many Western capitals, rhetorical sympathy for Iranian uprisings has typically stopped at statements and symbolic pressure, rather than the kind of decisive backing that could genuinely alter the internal balance of power.

In this setting, the broader geopolitical context becomes more conducive to a different kind of Western play: fostering a Turkic–Sunni hardliner axis channeled through Turkey and the wider Turkic space (OTS), reinforced by Saudi-backed Salafi networks stretching across Syria, the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, and anchored by Pakistan as a strategic hinge. The appeal is leverage without large-scale Western deployments—containing Russia and China (and even India) . Consistent with that logic, Western capitals may also be more inclined to prefer a “manageable” reformist drawn from within Iran’s system over an exiled restoration project such as Pahlavi. A regime-adjacent reformist figure like President Masoud Pezeshkian—an Azeri (Turk) with a Kurdish maternal background—can be interpreted as fitting that preference: signaling reform and national reconciliation while keeping change within boundaries. A new Iran under his leadership, free from the Mullahs, could even be integrated into that broader containment strategy.

A Hardline Sunni Axis Anchoring U.S. Strategy

The United States is also rearranging pieces in the Middle East’s sectarian puzzle to reinforce the regional order it prefers. In recent years, Washington has increasingly leaned into an emerging Sunni Arab alignment—effectively a hardline Sunni axis under Saudi leadership—as a counterweight to Iran’s Shiite-led bloc. This alignment overlaps with the broader “Turkic” strategy, creating layered structures of containment.

The contours of this U.S.-supported Sunni axis are visible in Yemen, among other arenas. Yemen has long functioned as a proxy battleground between Sunni powers and Iran, and in late 2025 a significant realignment unfolded within the anti-Houthi camp. Saudi Arabia—tacitly backed by the United States—moved to curb the UAE’s independent influence in Yemen in an effort to unify the fight against the Iran-aligned Houthi movement. Tensions between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had simmered for years, in large part because the UAE armed and funded the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a separatist faction whose agenda often undercut the Saudi-backed Yemeni government. In December 2025, these frictions escalated sharply as the UAE-backed STC seized control of key southern governorates such as Hadramout and Mahra, pushing out forces aligned with the Saudi-led coalition. From Washington’s perspective, this intra-Sunni split weakened the broader objective of containing the Houthis—and by extension Iran—so it was effectively resolved in Riyadh’s favor.

Saudi Arabia responded with unusual force, launching airstrikes against STC positions and deploying National Shield ground troops to retake contested areas. By January 2026, Saudi-backed Yemeni forces had reportedly recaptured the port city of Mukalla and surrounding zones after days of Saudi air raids. Local residents even welcomed the Saudi-aligned units as they displaced the separatists, whose advance had threatened to fracture the anti-Houthi front. Crucially, this assertive Saudi move appeared to proceed without U.S. pushback. American officials did not publicly oppose Saudi strikes against a militia tied to a coalition partner; if anything, restoring cohesion served U.S. interests by removing a distraction the Houthis could exploit. Washington’s priority remained weakening the Houthis and blunting Iran’s influence on the Arabian Peninsula. The United States also acted directly around the same period: in March, the Pentagon launched “Operation Rough Rider,” expanding air operations against Houthi-controlled territory under an anti-piracy rationale, with U.S. warplanes striking targets to degrade Houthi capabilities. Taken together with years of intelligence support for the Saudi-led coalition, these moves underscored Washington’s continued investment in a Sunni-aligned outcome in Yemen.

Seen through Yemen’s lens, a broader pattern emerges: the United States is actively reinforcing a militant Sunni axis led by Riyadh and aligned with other Sunni states. It has encouraged Saudi rapprochement with additional Sunni actors, including outreach to former rivals such as Qatar and Turkey. In strategic terms, this Saudi-led coalition functions as the southern anchor of an American containment ring—complementing the predominantly Sunni Turkic belt.

More recently, Syria has become another arena where this convergence is taking shape. Turkey (Sunni and Turkic) and key Arab states have increasingly coordinated to shape a postwar Syria aligned with Saudi Arabia and, in practice, influenced by Salafi-leaning ideological currents. The recent clashes between the Syrian army, consisting of many foreign fighters with Salafi ideology from the Caucasus and Central Asia, and the SDF—and the capture of two Kurdish neighbourhoods in Aleppo—are a case in point. The Salafi consolidation agenda of the United States collided directly with Kurdish leverage. The SDF’s autonomy and armed presence became an obstacle to the “one army, one state” project demanded by Damascus and backed by Erdogan’s Turkey. A merger and disarmament track existed on paper, but implementation stalled; when it broke down, the outcome turned coercive. Syrian forces moved to retake Kurdish-held districts, and the SDF ultimately withdrew and/or disarmed through evacuation arrangements, with reports of fighters departing and leaving weapons behind.

From this perspective, a unitary, highly centralized, Saudi-aligned Salafi Islamist state is more compatible with Israel’s preferences than a centralized Syria in which the Kurds—who are culturally, geographically, and linguistically closer to Turkey—retain meaningful self-rule and institutional leverage.

The Sunni axis strategy is not only for Israel. It also serves the U.S. goal of anchoring American influence in a multipolar Middle East. By bolstering dependable Sunni heavyweights, the U.S. builds a regional bloc that can resist not just Iran but also Russian or Chinese encroachment, not only in the Middle East but in the Caucasus and Central Asia, and even inside China – East Turkestan (Xinjiang). Moscow and Beijing have tried to court Gulf states and others, but a tight U.S.-Saudi-led coalition limits their inroads. For example, China’s tentative security partnerships with Gulf monarchies remain secondary as long as those states rely on U.S. weapons and protection. And Russia’s ambitions to act as a power broker (through OPEC+ or in Syria) are circumscribed when the core Sunni states coordinate more with Washington. perpetuates competition, as the U.S. leverages its Sunni partners to check adversaries at every turn.

Toward a Fraught Multipolar Contest, Not Peaceful Partition

Taken together, these dynamics paint a picture of a world inching toward multipolarity, but not the tranquil, pre-divided kind. The United States is clearly not reconciling itself to a diminished role or confining itself to one sphere. On the contrary, it is pursuing primacy by other means – knitting together region-specific coalitions, inserting itself in critical chokepoints, and leveraging ideological or cultural affinities (like Sunni unity or Turkic identity) to its strategic advantage. In each case – Middle Eastern power projection, meddling in Russia’s near-abroad, empowering the Turkic world, and backing a Sunni axis – the U.S. is asserting interests that cut across the notional spheres of its rivals. This undercuts the plausibility of any stable U.S.–China–Russia power-sharing accord. Instead of a grand bargain dividing the globe into tidy spheres, we see overlapping arcs of influence and competition. American-supported networks intersect and sometimes clash with Russian and Chinese-led ones. The emerging world order thus resembles a Venn diagram of contests more than a Risk board of static empires.