When George F. Kennan sent his “Long Telegram” from Moscow in February 1946, he could scarcely have imagined that nearly eighty years later, his logic of containment would be reborn—not against the Soviet Union, but against China. Yet history, like strategy, has a recursive quality. Containment was not merely a Cold War tactic; it was a geographic imagination, a way of inscribing alliances, corridors, and belts onto the Eurasian map to encircle a rival.

Last week, Azerbaijan and Armenia, under U.S. mediation, signed a peace agreement that resolved one of the most intractable disputes of the post-Soviet South Caucasus: the status of the Zangezur Corridor. This narrow 32-kilometer strip of land through Armenia, linking Azerbaijan’s mainland to its Nakhchivan exclave, has long been both a symbol of division and a potential artery of integration. The agreement, presented at a trilateral summit hosted by then–U.S. President Donald Trump, declared the corridor open under U.S. development rights and dubbed it the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP)”. This grants the United States exclusive development rights for 99 years to construct the TRIPP, where the U.S. will develop railways, energy transport infrastructure, and fibre-optic lines.

For Azerbaijan, the corridor solidifies its post-2020 victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, integrating its territories and enhancing its energy routes to Turkey and Europe. It reflects the “one nation, two states” principle shared with Turkey. For Turkey, the corridor known as the “Turan Corridor” is a crucial connection to Central Asia, fulfilling a long-held vision of pan-Turkic geography that Ankara has aimed for, and strengthening regional leadership. For the United States, however, the Zangezur Corridor is not merely a transport project: it is the beginning of a new geopolitical strategy to contain China.

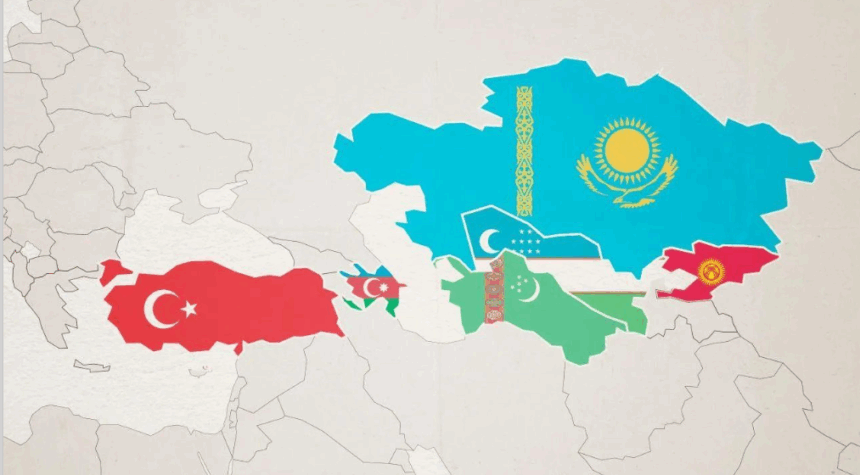

In this regard, the Zangezur Corridor represents the first operational step in constructing a “Turkic Belt”—a geostrategic arc of Turkic states stretching from the Balkans to Xinjiang (East Turkistan) being shaped by a convergence of U.S. strategic imperatives, Turkey’s assertive regional vision, and the institutional consolidation of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). What is unfolding is not only an infrastructural competition over the Zangezur corridor, but also a civilizational reordering in which Turkic identity is harnessed as both connective tissue and a geopolitical wedge.

The main goal of the Turkic Belt is to contain China while reducing Russia’s influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus, as well as Iran’s role in the region. Both Russia and Iran are key allies of China, which the United States views as its greatest adversary. Following the peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, media coverage primarily focused on how this deal represented a significant setback for Russia and Iran. However, it largely overlooked the overarching U.S. objective of countering China, which is regarded as the biggest threat to U.S. interests. If Kennan saw Moscow as the “center of political force,” Washington today sees Beijing as the systemic rival whose influence must be diluted not only across Eurasia but also globally.

The Kennan Paradigm and Green Belt Strategy

Kennan’s “Long Telegram” (1946/1987) and his subsequent “X Article” (1947) codified the principle of containment: the belief that Soviet expansionism had to be met not by accommodation but by patient, multidimensional resistance. The key was geography—to deny Moscow access to warm waters, industrial bases, and strategic chokepoints. This logic was institutionalized in NSC-68 (1950), which explicitly called for the U.S. to project economic and military strength globally to block Soviet influence. NSC-68 understood infrastructure—railways, pipelines, ports—as political tools. Whoever controlled Eurasian arteries controlled the global balance.

In the 1970s, as Soviet power pressed into Afghanistan and beyond, U.S. strategists revived containment with a new twist: the Green Belt Strategy. The Green Belt thesis posited that U.S. strategists — from Zbigniew Brzezinski in the Carter administration to elements within Reagan’s national security team — sought to harness Islamic identity and political activism across Eurasia to counter Soviet influence. While archival evidence remains inconclusive, many scholars have treated the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the Afghan jihad, and U.S. relations with conservative Muslim regimes as components of an implicit or explicit containment strategy, one that deployed religion as a counterweight to Marxism-Leninism. Critics, however, have argued that the Green Belt was never a coherent doctrine, but rather a retrospective label applied by journalists and political commentators to a series of ad hoc American responses to crises. Revisionists have gone further, suggesting that Kennan’s original vision of containment, rooted in patient political-economic pressure rather than ideological engineering, was distorted by later practitioners who leaned heavily on proxies, belts, and regional identities. This historiographical ambiguity, however, does not negate the utility of examining the Green Belt as a conceptual precursor, for it reveals how Washington has recurrently turned to cultural, religious, or civilizational geographies as scaffolding for containment.

In the case of the Turkic Belt, the geopolitical imagination is shaped less by religion than by ethnicity, language, and civilizational kinship. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Turkic peoples from Anatolia to Xinjiang (East Turkistan) have been seen by Ankara, Baku, and increasingly by Western observers as a potential connective tissue across Eurasia. The institutionalization of this vision in the Turkic Council (later the Organization of Turkic States –OTS) gave it an intergovernmental framework, while Turkey’s activism in Central Asia and the Caucasus following independence created the foundation for Turkic solidarity. Yet the Turkic Belt only acquires strategic significance within the broader rivalries of the great powers.

The debates over whether Kennan himself would have endorsed such identity-driven strategies remain lively. Kennan’s 1947 “Long Telegram” and subsequent “X Article” argued for the gradual containment of Soviet expansion through political and economic pressure, but avoided prescriptions based on religious or ethnic mobilization. Indeed, Kennan later lamented that his nuanced proposals had been transformed into militarized doctrines, which bore little resemblance to his intent. Yet the persistence of the “belt” concept reveals how American strategists, both then and now, often extend containment into cultural-geographic terms. The Green Belt was thus less Kennan’s than Brzezinski’s creation, with its emphasis on exploiting the Islamic awakening as both a shield and a sword against Soviet encroachment. The Turkic Belt, similarly, is less a coherent Kennan-style grand strategy than a confluence of U.S., Turkish, and Azerbaijani interests that may nonetheless congeal into a systemic mechanism of containment against China.

Zangezur Corridor and Turkic (Turan) Belt

The Zangezur Corridor serves as the linchpin and the starting point of this strategy. Located in southern Armenia, the corridor connects mainland Azerbaijan with its exclave of Nakhchivan, which borders Turkey. By completing this missing link, Azerbaijan ensures uninterrupted land access to Turkey. In return, Turkey gains direct overland access to Central Asia, reducing reliance on Georgia’s often congested routes, a corridor referred to by Turks as the “Turan Corridor“. The agreement, however, goes beyond local utility: the United States has taken development rights, branding it the “Trump Route,” a name signalling both the administration’s personalist branding and Washington’s intent to wield the corridor as a geostrategic tool. In the post-Ukraine South Caucasus, the collapse of Russia’s coercive leverage has produced both a vacuum of authority and a new arena for U.S.-sponsored projects such as the Zangezur Corridor. This vacuum has allowed Washington to step in not only as a mediator but also as a long-term guarantor of connectivity, embedding its influence across a region once tightly bound to Moscow’s orbit.

Iran and Russia, meanwhile, perceive the corridor as a direct threat. Both Moscow and Tehran have historically been wary of pan-Turkism. Russia fears the empowerment of Muslim and Turkish minorities, while Iran is concerned about the empowerment of its own Azerbaijani minority and the potential erosion of its role as a north-south transit hub. Russia, already weakened by its faltering war in Ukraine, views U.S. penetration of the Caucasus as a further loss of influence in its former imperial periphery. Both states, however, face structural constraints in countering the project: Iran remains under heavy sanctions, and Russia’s resources are stretched thin. The containment of these two actors indirectly serves the U.S. objective of containing China, since both Moscow and Tehran are Beijing’s strategic partners. Weakening them thus fragments China’s continental support network.

From a logistical perspective, Turkish officials and trade associations highlight how Zangezur integrates with the broader “Middle Corridor” that runs from China through Central Asia, across the Caspian, into Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and onward to Europe. Yet where the Middle Corridor has been plagued by delays at Georgian customs and underinvestment, Zangezur offers a streamlined route that reduces transport costs and delivery times. UTIKAD, Turkey’s leading logistics association, has hailed it as the potential backbone of a “Eurasian logistics bridge.

The geopolitical implications, however, transcend trade facilitation. By inserting itself into the Zangezur corridor, Washington has created a potential chokepoint within China’s BRI network. China’s own Middle Corridor investments—including the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, under construction since 2023—envision a seamless route into the South Caucasus. In principle, Zangezur could complement these ambitions, but under U.S. oversight, it represents a dilution of Chinese regulatory autonomy and an exposure to political leverage. A crisis in U.S.–China relations could see the corridor weaponized against Beijing, just as maritime chokepoints like the Malacca Strait have long been considered vulnerabilities.

Moreover, the Zangezur corridor is not only shaped by Western and Chinese interests but also reinforced by the institutional solidarity of the Organization of Turkic States. Stronger integration under the OTS provides a ready-made framework of coordination—economic, political, and potentially military—that magnifies the US’s leverage. If consolidated, this solidarity could serve as both a balancing mechanism against China’s expanding global footprint and a vehicle for aligning regional security concerns with broader strategic agendas. In such a scenario, OTS-driven initiatives would not simply complement U.S. oversight but could actively be mobilized in times of geopolitical confrontation, offering Washington a strategic instrument to constrain Beijing’s influence along the Middle Corridor and beyond, including the Middle East and Africa.

Against this background, the containment analogy becomes clearer when viewed through the lens of American grand strategy. Kennan’s doctrine of containment, articulated in 1947, argued that the United States should apply “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.” In the Islamic Green Belt strategy of the late Cold War, Washington embraced proxies and identity politics to pressure Moscow’s southern tier. Today, the Turkic Belt represents an evolution of this logic: an identity-driven coalition, this time based on Turkic solidarity rather than Islam, stretching across Eurasia as Zangezur, marking the beginning of a “long-term (99 years or longer), patient, but firm and vigilant containment” of China along with its main allies, Russia and Iran.

Can the Turkic Belt Succeed Without the Gülen Movement?

In today’s world of renewed great-power competition, the Gülen Movement’s once-vast global network lingers as an untapped reservoir of soft power. Through its schools and cultural institutions, it has long promoted education, modernization, and civic leadership—values that still give it the potential to serve as a quiet partner for the West in countering the authoritarian models championed by Beijing and Moscow.

The challenge is not in recognizing this potential but in finding the right way to engage it. A careful, strategic revival—one that leans on the movement’s educational and cultural roots rather than overt politics—could give the West a long-term foothold in places like Central Asia and Africa. In these regions, where influence is increasingly contested, the Gülen network could once again help anchor democratic norms, civil society, and open governance as viable alternatives to the authoritarian paths being laid down by rival powers.

Yet, any such strategy will remain incomplete and less effective if Gülen Movement itself—historically Turkey’s greatest soft power vehicle—is absent from the equation. The movement was not simply a transnational educational network; it was also the single most important instrument of Turkey’s “smart power“, projecting Ankara’s cultural and intellectual reach far beyond its borders. For the Turkic peoples in Central Asia, this network embodied the bridge between their post-Soviet aspirations for modernization and Turkey’s role as a civilizational leader. Within the emerging “Turkic Belt” project, where identity and connectivity are increasingly mobilized as strategic resources, the absence of Turkey’s strongest soft power tool would leave the framework hollow.

For any long-term strategy to hold, the West, the Turkic world, and Turkey itself must see the revitalization of the Gülen Movement not as a side issue but as a core requirement. The movement’s network is more than an accessory to policy; it is one of the few proven tools of soft power that can shape minds, build trust, and nurture leadership across borders. Without it, efforts to contain authoritarian influence in Eurasia will struggle to gain real depth or credibility—leaving the vision of a Turkic Belt as little more than a fragile framework, impressive in theory but weak in practice.

By: GEOPOLIST – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics