Summary by Geopolist – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics:

- The EU has started to rebuild the connection between its security and economic policies, following its strategy for economic security and the de-risking paradigm.

- However, focusing only on risk reduction is short-sighted and prevents the EU from effectively managing its position in the global economy at a time when other countries’ ambitions threaten to limit its options.

- The EU should use the beginning of the new institutional cycle to improve its strategy and make it stronger. This new strategy should help the EU strengthen its position in the global economy and deal with future challenges from the US, China, and Russia.

- To achieve this, the EU needs to take a proactive approach that goes beyond just considering risks. It should also create a more geopolitical and less isolated structure and reassess the traditional principles that govern the most important supply chains.

- To implement this strategy, the EU should improve its knowledge and intelligence in critical supply chains, update its working methods, introduce new economic security standards and establish new partnerships along strategic supply chains.

The EU’s geoeconomic awakening

The feeling of doom and gloom about the economy is palpable across much of Europe. Industry groups, CEOs, and politicians have been sounding the alarm for months, as the European Union appears to fall behind the United States and China on economic metrics ranging from productivity gains and innovation output to research and development investments and capital market scale. Former Italian prime ministers Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta have lent political weight to the idea that the EU’s cards in the global race for economic growth, industry, and transformation are much weaker than those of its rivals and that it needs – in Draghi’s words – a “radical change” if it is to keep up. In April, European leaders heeded those concerns at a special European Council and called for a new “competitiveness deal” to close the economic gap with their rivals. The next commission is set to make competitiveness one of its top priorities.

A strong economy is indeed the foundation of European prosperity, influence, and security. But making the EU “competitive” alone would not automatically improve its geoeconomic position. A truly geoeconomic EU will need to do more than offer better business opportunities for its companies or cut bureaucratic red tape. Europe’s geoeconomic position is equally co-determined by its ability to capture and defend technological leadership positions, maintain shock-resilient production capabilities, and restructure its most vital economic networks along new geoeconomic fragmentation lines. In this reality, even the most ardent European free traders are coming to terms with the fact that prosperity and security are complex privileges, the maintenance of which may require a more managed approach to certain economic and technological challenges.

European leaders have therefore endorsed an additional leg to their economic agenda to address these diverse geoeconomic challenges: “de-risking”. To put de-risking into practice, the European Commission’s June 2023 economic security strategy laid out a blueprint for how the bloc can identify risks and the guidelines available to mitigate them. It addresses risks arising from supply chain disruptions, economic coercion, the unwanted leakage of technology, and critical infrastructure disruptions.

De-risking certainly sounds safe and pragmatic, and promises only limited and cost-effective incisions into the economy, but it masks the complexity it purports to address. Firstly because difficult trade-offs abound when trying to limit Europe’s risk exposure. Limiting the risk of depending on third countries for critical raw materials or clean technology inputs, for example, may expose the single market to other risks, such as higher costs for the production or installation of clean technologies.

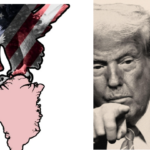

Secondly the ambitions of other powers are calling the practicality of de-risking into question. Washington, for example, appears bent on tightening the trade and technology screws on China ever further as it pursues its national security goal of maintaining technological leadership. Its measures to achieve this, from export, investment, and financial controls to subsidies that bend supply chains towards American shores, may not fully align with Europe’s own designs to decrease risks. Beijing, meanwhile, is doubling down on its own national-security-driven de-risking agenda. This effectively seeks to limit the share of European inputs into China’s industries and simultaneously increase Europe’s reliance on China’s own strategic goods and services by supporting major production expansions in technologies and industries which form the backbone of the emerging global economy. Paired with the possibility of any of a number of geopolitical events, from the re-election of Donald Trump as US president to a naval incident in the South China Sea, these dynamics could throw any semblance of an ordered European de-risking agenda into disarray.

European leaders have a long way to go to transform their new agenda items on competitiveness, de-risking, and economic security into a solid geoeconomic strategy. The new EU institutional cycle offers an opportunity to do that.

In this policy brief, we set out why the EU’s current approach, encapsulated in its economic security strategy, does not yet offer the right guidelines to strengthen Europe’s geoeconomic position or deal with the biggest geoeconomic challenges in the coming years – America’s strategic trajectory, China’s securitised economy, and Russia’s war. Based on these lessons and input from ECFR’s flagship geoeconomic strategy group, we then offer three guidelines to upgrade the strategy into one that can strengthen Europe’s geoeconomic position vis-à-vis other powers. Finally, we recommend some building blocks for how European policymakers can operationalise this process.

Where the economic security agenda falls short

Risks are at the forefront of the EU’s evolving outlook on the global economy, which is increasingly defined by great power competition, fragmentation, and disruptions. In addition to identifying the major risk categories of supply chain disruptions, economic coercion, the unwanted leakage of technology, and critical infrastructure disruptions, the 2023 economic security strategy set out three guidelines for mitigating risks: promoting, protecting, and partnering. This risk-based approach has become the dominant concept through which the EU attempts to re-organise its economic actions.

While the 2023 strategy was comprehensive and ambitious, the EU has struggled in the year since to advance it fully. The risk assessment process, led by the European Commission, has proven difficult to operate, at times causing frustration both in European capitals and among businesses due to perceived unclear objectives and its vast scope. Meanwhile, the commission has struggled to transparently communicate what its desired end goals are.

In January 2024, the commission then released a first suite of proposals to strengthen the EU’s economic security, including proposals to revamp the EU’s 2019 investment screening regulation and enhance research security across the bloc, as well as three white papers on assessing risks related to outbound investment, reforming the 2021 dual-use export control regulation, and supporting research and development in technologies with dual-use potential. This package focused primarily on addressing narrow national security risks related to technology leakage, but stopped short of aiming for more comprehensive reforms. This segregation is a problem as risks hardly emerge in isolation. Risks related to technology leakage, for example, could exacerbate supply chain resilience, coercion, or critical infrastructure risks, meaning pulling the lever on one will have implications for the others.

In addition to addressing the four risk categories independently, rather than as one challenge, the EU’s January economic security package focused almost exclusively on the “protect” agenda (with the exception of the proposal for more research and development funding for dual-use research). A broader view, which would assess economic security in light of Europe’s battle over techno-industrial high grounds, was missing.

This is not to say the EU has been sitting on its hands. It has launched several initiatives aimed at promoting and partnering. But these have been either limited in scope or siloed from other intiatives – or both. Notable “promote” tools include the 2023 European Chips Act which aims to mobilise some €43 billion of public and private investments into the continent’s shrinking semiconductor ecosystem; a Net Zero Industry Act and a Critical Raw Materials Act which aim to boost the EU’s production capabilities for strategic clean technologies and the raw materials required to produce them; and a Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP) to provide financial support for clean technologies and defence manufacturing capacities (which was however significantly scaled down in its financial ambition). Although often ambitious on paper, these acts rely on national state aid exemptions to promote industry, and are only loosely coordinated by Brussels. A joined-up European industrial policy, in which goals, capabilities, and supply chains are defined beyond national borders, is effectively missing.

The “partner” dimension of the economic security agenda reveals a similar story. The EU has developed a range of new partnership formats primarily to address risks, including more than a dozen new raw materials deals; new formats for climate diplomacy; Global Gateway to direct resources to strategic partners; and technology diplomacy formats, notably the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) with the US and India and digital partnerships with Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. However, these partnerships remain largely detached from the EU’s internal risk measures, such as those targeting technology leakage or industrial upgrading.

In effect, it remains unclear how the protect, promote, and partner elements relate to one another. For example, plans to promote clean technology manufacturing in the EU were not linked to credible protections for industrial start-ups against the deluge of cut-price equipment and goods from China (the recently announced tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles may be a turning point in this regard). Neither is it evident how the EU intends to align its own promote goals with those of its partners in emerging economies, which are themselves seeking stronger positions in the key supply chains of tomorrow and could find themselves penalised by the EU’s measures. Serious anger among emerging economies over the European Green Deal tools, such as the carbon border adjustment mechanism and the de-forestation law, demonstrates the challenge of designing de-risking measures which actually partner with, not punish, emerging economies.

The EU’s economic security agenda so far is too narrow, reactive, and defensive. And it is not clear how it hopes to address the difficult trade-offs with other goals, such as greening its economy or boosting its technological edge or prosperity, as outlined recently by our ECFR colleagues. The current approach lacks a strategic vision and concrete goals to make sense of the myriad trade-offs created by the different initiatives, even today. But three major geoeconomic challenges on Europe’s doorstep could further tear it apart. The EU needs to draw the right lessons from these if it is to adjust its course and ensure its strategy is equipped for the evolving world.

A hostage to fortune

The US factor

The US presidential election later this year will have a colossal effect on Europe’s geoeconomic position. As ECFR colleagues have explored in extensive scenario exercises, a second Trump term would likely see the US reset its trade relationship with China as a top national security priority, taking an even tougher stance. This could have a number of consequences. Republican lawmakers have already tabled bellicose ideas in Congress such as repealing China’s permanent normal trade relations status. Meanwhile the former president has boasted of introducing a 60 per cent tariff wall on most Chinese imports, coupled with a universal baseline tariff of 10 per cent on all imports, including those from allies. More recently Trump suggested he would outdo the current administration by imposing a 200 per cent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles – double Biden’s proposed 100 per cent tariff. Even if a potential Trump administration did not implement such policies, global businesses would likely take more extreme measures to prepare for a potential trade war than they did during Trump’s first term. China, meanwhile, could for example significantly increase its export pressure on Europe or use the occasion to boost its charm offensive on Europe by offering economic and political cooperation – such as an EU-China green economy agreement.

Trump would also likely set out to make deals with EU capitals directly. These deals could well make US security provisions to the EU conditional on economic concessions, further eroding the separation between economic and security interests. For example, a Republican administration could connect security and financial guarantees for Ukraine to demands for a more forceful European approach to curbing China’s economic and technological advancement. By disregarding any EU competencies and speaking directly to member states instead of the European Commission, Trump would likely undermine a common front.

A re-election of Joe Biden as president would undoubtedly be a better outcome for Europe, likely preserving the vital unity of the transatlantic alliance over Russia’s war on Ukraine. But another Biden term would also challenge the EU’s approach to economic security and de-risking. Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan speaks of a “small yard” and a “high fence” to describe the US trade and technology restrictions aimed at China, which are designed to only limit the trade of a narrow set of “force-multiplying” technologies, those which drive the innovation, production, and capability gains in nearly every emerging industry, such as the most advanced semiconductors. This approach appears much in line with Europe’s own narrative of limited, cost-effective de-risking. On the ground, however, the Biden administration has maintained, expanded, and streamlined trade and technology restrictions covering a growing range of items and industries which fall under the purview of national security. New data security measures and a cybersecurity investigation into connected systems conducted earlier in 2024 could, for example, cause further disruptions to a wide range of industries and the products, services, and data flows in their supply chains, from connected vehicles to the biotechnology sector. Because connected ecosystems rely on strong interconnectivity of devices, people, and data flows, “there are no small yards in regulating the digital economy,” as one recent report warned.

The Biden administration has also become much more assertive in pushing its European allies to adopt similar restrictions, despite disagreements over the effectiveness and utility of more controls. Meanwhile, the vast financial firepower of the Inflation Reduction Act, which incentivises clean technology investors to set up shop in the US through its generous tax cuts and domestic manufacturing requirements, continues to bother many Europeans who fear a race to the bottom with the US in the green industries of the future (however unlikely this may be). In addition, few American policymakers from either side of the political spectrum still support a global trading regime centred around the World Trade Organization. Instead, many would prefer the development of a US-centred trading bloc for allies and partners.

Whatever the outcome of the US election, it seems set to affect the EU’s geoeconomic options. The EU’s economic security agenda appears ill-equipped to deal with this challenge. Europeans are championing a technocratic and data-driven approach to economic security, which sees de-risking as a narrow and precise affair to identify and then mitigate existing risks such as trade dependencies. Meanwhile, the US (as well as China) has framed and will continue to frame economic security geopolitically, understanding that economic competitiveness and technological leadership are essential factors of its relative power vis-à-vis China and, therefore, matters of national security.

The China factor

China’s increasingly securitised economy is a geopolitical challenge for Europe, not just a trade risk. After several decades of sky-high growth, China’s recent economic malaise is well documented: the stock market has been in free fall for over three years and wiped out trillions of dollars-worth of investment; its real estate sector is in deep trouble, with Chinese lenders writing off hundreds of billions of loans; and new foreign investment is at a historical low point.

Despite these challenges, Beijing’s leadership remains committed to a security-driven economic policy, through which it aims to increase national control over parts of the global economy it deems crucial to its position of power. China has been de-risking for decades, just under different banners. Beijing’s strategic theory “two markets, two resources” dates back to the 1980s and distinguishes between the domestic market and resources – which it aims to insulate – and international market and resources – which it aims to take advantage of. The same idea has more recently been encapsulated in its “dual circulation” strategy. Today, this has a final layer – “going out” – which involves not only exports but what some call “whole industrial chain output”: a politically coordinated and comprehensive push to export and expand various segments of strategic supply chains. Alongside the products themselves, this effort involves a wide range of services, management models, trade logistics, and cultural exchanges. Chinese electric vehicle exporters, for example, are gaining more influence over industrial supply chains, technology standards, trade flows, business models, and global commerce writ large. Today outflows of Chinese investments abroad substantially exceed inflows of foreign direct investment.

Alongside its longstanding goal of increasing economic and technological self-reliance, Beijing is trialling new strategies to expand its technological advantages – goals which were reaffirmed by China’s Central Committee and the State Council in 2023. “Technological innovation has become the main battleground of the global playing field, and competition for tech dominance will grow unprecedentedly fierce”, Xi remarked in 2022. In addition, China is working to be able to retaliate to its rivals’ economic statecraft. China’s dominance in the production of intermediate goods (such as electronics and machinery components) is particularly strong and provides it significant leverage in managing any European attempts to de-risk. Furthermore, ironically, de-risking supply chains from China can drive increased demand from countries using Chinese inputs. Being the primary supplier of intermediate goods not only helps China offset export losses, it also provides it with more significant, albeit less visible, leverage. Western-led sanctions and controls are therefore accelerating and refining these Chinese securitisation developments.

Beijing’s desire to take up leading industrial positions is further enabled by the major structural imbalance in the Chinese (and global) economy, which is focused on creating additional supply rather than domestic demand. China’s financial savings, once used to support its infrastructure and real estate sector, are now channelled to manufacturers, particularly in fast-growing and strategic industries like electric vehicles and semiconductors. This, however, has the potential to create excess capacities that the Chinese market cannot absorb, and Beijing does not seem keen (or able) to spur higher domestic consumption. The effects of this economic policy could cement China’s already unrivalled manufacturing power for years to come, and its excess industrial production capacity in industries ranging from clean energy technology and petrochemical products to shipping, machinery, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and legacy chips, could re-wire the global economy. China’s annual manufacturing capacity for solar modules and battery cells, for example, will be around double the level of global demand (consistent with reaching net-zero emissions) by 2050. The US has traditionally absorbed a large chunk of China’s trade surplus, but now is unwilling to forego its own market share in emerging future industries, such as batteries and electric vehicles. The brunt of these goods will therefore likely flow to Europe and emerging economies like Brazil, India, Mexico, and Vietnam, although they too are beginning to raise trade barriers on China.

The EU’s economic security agenda hardly prepares it for these powerful dynamics. European countries have significantly adjusted their relations with China in recent years and become more realistic, pragmatic, and hardened as Beijing’s charm offensive has increasingly fallen on deaf ears across the continent. However, varying degrees of risk tolerance and trust vis-à-vis China remain within Europe, which obscures the scale of the China challenge for the EU’s geoeconomic position. And the EU’s de-risking agenda largely turns a blind eye to China’s own de-risking strategy.

The EU has recently raised tariffs on Chinese electric vehicle imports and has opened several other trade defence investigations. But it will need a more systematic agenda to cope with China’s own fired-up economic strategy. For example, while it has defined an agenda to upgrade its own battery production capabilities, the ambition pales in comparison to the challenge. Despite the European Commission and the UK approving €7 billion in subsidies for battery manufacturing since the start of 2022, China’s excess capacity has set off a price war which many smaller players may not survive. Even Europe’s biggest battery makers struggle to compete with a deluge of cut-price equipment and goods from China.

The Russia factor

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine catapulted the EU’s economic and security policy into a new era, testing European security more than it had been tested since the end of the cold war. Sweden and Finland have joined NATO and member states are increasing defence spending and delivering military equipment to Ukraine. Russia has weaponised its energy deliveries to Europe, while EU member states have gradually weaned themselves off their heavy reliance on Russian fossil fuels. In response to the full-scale invasion, the EU has imposed 13 rounds of sanctions on Russia over the past two years.

These events have affected Europe’s geoeconomic position in several ways. Energy warfare by Russia and the EU’s diversification of its suppliers have led to temporary energy price shocks that drove up European inflation in 2022. The EU’s unprecedented sanctions regime has required it to constantly adapt its measures and deal with the contentious topic of tackling circumvention. It has pushed Europeans to consider using secondary sanctions to deter companies in third countries from facilitating trade with Russia and will continue to raise hard questions about how to treat other countries, such as China, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, or even India, when they do not adopt European measures and are found to be trading with Russia in areas Europeans would like to curtail.

Yet despite the gravity of the EU’s sanctions policy, it lies outside the purview of the economic security agenda, even though de-risking the links between the EU and its rivals will inevitably diminish the deterrence effect of sanctions threats. An effective sanctions strategy depends on credible leverage to enable it to deter or, if deterrence has failed, to deny. Economic deterrence and denial have become vital in Europe’s security posture against Moscow – but they are absent from Europe’s wider economic security debate. Economic deterrence and economic leverage are two sides of the same coin. If Europeans are serious about the first side of the coin – which they should be given the dramatic costs of the failure of deterrence with Russia – then they need to ensure that their economic security strategy allows them to gain and maintain the second side. This must also include deterring China from enabling support to Russia.

Finally, Europeans will have to consider how a long-term commitment to Ukraine’s defence and a pledge to finance its reconstruction will pose a completely new challenge to its economy. Unless the EU’s economy is thriving, it will be increasingly difficult to unite member states around support for Ukraine’s war effort and reconstruction. Russia’s war on Ukraine, therefore, demands a rethink from Europeans in several geoeconomic dimensions. It requires minimising threats to its economic growth trajectory to meet the challenges posed to sustaining Ukrainian support and building long-term economic resilience.

Upgrading the EU’s economic strategy

The economic security and de-risking paradigms which the outgoing European Commission has helped bring to life have been major achievements in readjusting Europe’s geoeconomic outlook. They have started to rekindle a dormant understanding that security and economic policies can no longer be disconnected and offer different tactics to deal with risks. But they have so far failed to offer ways to manage trade-offs between economic growth, national security, and climate change, and struggled to tie the protect, promote, and partner elements together.

Furthermore, other global powers – from the US to China to Russia – are using economic tools in service of their geopolitical agendas, reshaping technological and military trade lines to their benefit. In doing so, they are dictating the EU’s options too. If the EU is to keep pace with other geoeconomic players, it needs therefore to reconsider the parameters of its economic agenda, not just its tactics. Those tactics – protect, promote, and partner – can provide some alliterative inspiration for this process. To strengthen the EU’s geoeconomic position and equip it to manage the challenges of the future, the EU needs to upgrade its strategy to be proactive, political, and principled.

Making it proactive

Europe’s economic security mindset and toolbox has focused on reacting to risks that are already present, such as import dependencies. This is insufficient to prepare the bloc for other powers’ geoeconomic agendas. As discussed above, the US agenda, for example – no matter its president – is about winning the competition with China over technological, economic, and military leadership. China meanwhile is de-risking from the West by pursuing different asymmetric strategies, such as strengthening its positions of control, which provides it with leverage and undermines Europe’s own de-risking goals. Though the strategies of the great powers differ, they have at least one element in common: they are proactive and go far beyond mere risk mitigation.

In a world in which interdependence will remain a reality, de-risking alone is a recipe for failure. In such an environment, the EU needs its own leverage, as well as the political ambition to use this leverage proactively to shape the bloc’s position in the supply chains and industries of tomorrow. It therefore needs to upgrade its reactive de-risking strategy to a proactive geoeconomic strategy that focuses equally on its strengths.

The EU’s geoeconomic strength is not simply the size of its single market or the sales orders of its companies. Because competition is above all over control and access to key technology and industrial supply chains, strength and the ability to act derive from access to assets which enable the fusion of technology and industry along those supply chains. Assets include, among other things, advanced manufacturing facilities, research and development centres, specialised equipment, raw material inputs, and linkages between different supply chains.

Identifying critical technologies for economic security, as the EU has begun recently, is a good starting point to build a more proactive geoeconomic agenda. However, focusing on the final product will not be enough, leaving the EU dependent on other assets further upstream. Consider the battery sector, in which Chinese equipment suppliers hold powerful manufacturing and innovation assets which allow Beijing to steer and counter European de-risking efforts. Or the semiconductor sector, in which the EU has focused its attention on high-end advanced chips, while China could soon dominate in a number of simpler so-called legacy chips – crucial for a wide range of applications such as in automotives, industrial automation, and communications. The EU, therefore, needs a mindset shift from understanding risks to understanding which positions of strength its industries command (or could gain) that could allow it to proactively shape geoeconomic dynamics along contested supply chains.

Making it (geo)political

While identifying strengths requires technical supply chain knowledge, using leverage requires political ambition – that is, knowing how the EU wants to exploit its strengths and assets. For this, the EU needs to define geopolitical goals, not just technical risks, which can help steer how the bloc uses its own geoeconomic levers to shape the competition with other powers over innovation, production, and trade along the most critical supply chains. One geopolitical goal should be to ensure the EU remains an indispensable technology player for other powers, especially for China. Preventing widening Chinese support for Russia’s war, as well as building a resilient economy that can deter and respond to the destabilising threats posed by Vladimir Putin’s Russia, are other geopolitical priorities which require a more direct link to Europe’s economic policy. On the basis of such geopolitical goals, the EU must probe and direct its geoeconomic toolbox, as it has begun to do for the goal of the green transition. This would enable a more systematic strategy – far from the EU’s current game of risk whack-a-mole.

For a more geopolitical strategy to work, the EU will need to overcome its fragmented policy silos. Unlike during the cold war, when strategic knowledge relied much more on weapons systems and battalion stations, this geoeconomic age requires in-depth intelligence of supply chains, technologies, industries, and trade patterns. Gathering and sharing sensitive information between industry and governments, between EU member states and the European Commission, and between the EU and its allies is a strategic capability which is foundational to a more coherent, geopolitical approach. Simultaneously, leaders must create a political overview of how geoeconomic challenges are interlinked, from Russia-China ties to export controls and new partnerships with countries that are key players in priority sectors. This is hardly possible using today’s working methods.

Resetting the principles

The tremendous impact great power competition is having on the global economy means that powerful countries are dictating new rules and principles for economic exchanges. The effect is not a simple de-globalisation or decoupling-at-large, but forms of “re-globalisation” through which strategic supply chains are re-wired.

The EU has not been absent from this dynamic, using its market to shape global supply chains in line with its preferred green and digital standards, for instance. For its de-risking objectives, however, it has been less willing to become a standard-maker, largely leaving the field to others. While the bloc rightly contemplates the potential unintended consequences of its green trade principles, its inaction could leave it as a standard-taker.

Firstly, Europeans are keen to distinguish between two types of threats: those related to economic competition (like strategies to dominate key industries through unfair trade practices) and those related to national security (such as sensitive technology falling into military hands). But this distinction is becoming ever more tenous as other countries target entire industrial supply chains as a basis for military advantage. The defence-industrial challenge exposed by Russia’s war on Ukraine is instructive, with the security threat extending deep into the single market. Europe’s production of vast amounts of dual-use goods – which can be used both for military and civilian equipment, such as ball bearings, electronic engines, and pipes – has become its Achilles heel. Many of the components built into military equipment worldwide originate in the EU or other Western economies. Clean technologies also illustrate the growing overlap between national and economic security. Technologies such as connected vehicles (like electric vehicles) and solar inverters (which enable the energy generated by solar panels to be fed into power grids) are primarily viewed as an economic challenge. But they can transmit and control data flows that encroach on matters of national security and cybersecurity. Resetting economic security principles will therefore require a widening of the national security aperture beyond traditional military threats and goods.

Secondly, hopes that businesses will themselves re-jig strategic supply chains, such as those for critical minerals or battery components, even if doing so exposes them to higher costs are proving unrealistic. Consider for example the EU’s strategy to bolster alternative raw material suppliers in Africa and Latin America by making investment in these countries easier for EU companies. If these alternative suppliers cannot compete on price with China’s massive scale mining, processing, and manufacturing operations, European buyers are unlikely to favour them. The EU’s economic security strategy must therefore also ensure that the single market offers opportunities to sell diversified supplies not only on the principle of cost. Economic security principles should determine participation in a strategic supply chain based on national and cyber security, climate, resilience, technology security, and critical infrastructure standards.

To counter any negative reactions to its economic security agenda, the EU must put together a more comprehensive offer for the global south and key emerging economies that includes, in addition to market access, financing and innovation cooperation that enable countries to meet the EU’s economic security and climate standards and thereby deepen their integration with the EU. For each strategic supply chain, the EU must identify international partners which can support a more resilient supply chain and rally its full toolbox to ensure that cooperating with the EU along these supply chains offers economic opportunities for them.

Operationalising the EU’s wider strategy

These three principles should help lift the EU’s economic security agenda to the next level and raise the bloc’s profile as a geoeconomic actor. When it comes to building a more proactive, political, and principled strategy though, the EU needs to approach all aspects of its economic and trade policies with a focus on competing in the most coveted industries and supply chains. This will necessitate a comprehensive approach across Europe, rather than one that relies on a limited set of tools to address risks. We recommend that the European Commission and member states begin with the following policy building blocks.

Build an EU techno-industrial intelligence compact

Techno-industrial intelligence – the ability to identify the technologies and assets which make up industrial ecosystems, the supply chains they depend on, and who may be using these technologies and for what purpose – is among the most important strategic enablers in the geoeconomic age, and the EU is lacking it. Emerging technologies such as AI, synthetic biology, advanced materials, and quantum are evolving at record speed, and those who lead gain shaping power and security benefits. Upgrading the EU’s intelligence capabilities is therefore a vital precondition to becoming a more proactive geoeconomic player.

The risk assessments into technology ecosystems that the commission and member states have begun serve as a useful starting point. But they have also demonstrated the EU’s many shortcomings when it comes to collecting and sharing relevant information. To improve this ad hoc process, the EU should upgrade it into a techno-industrial intelligence compact, which would commit to enhancing and pooling analytical capabilities both in Brussels and national capitals. This new structure should include experts on industry and security to determine how the commission and member states can generate relevant techno-industrial intelligence on a continued basis. It would enable the EU to expand its knowledge of risks and strengths and unite the different risk assessments which are currently treated largely in isolation and with limited resources.

Reform the EU’s economic security architecture

The EU’s current economic security architecture is ill-equipped to support a more proactive, political, and principled agenda. Efforts are needed to break through policy silos more effectively. Firstly, the European Commission needs a stronger coordinating role between the different economic security policy portfolios. An Economic Security Directorate in the Secretariat General could oversee and support a more streamlined implementation of the commission’s strategy. Additionally, an executive vice president for geoeconomics, as ECFR has previously proposed, should take on a coordinating role between the different commission portfolios supporting its geoeconomic agenda, such as the directorates for trade, internal market and industry, external action, and international partnerships. This position would also serve as a single access point for member states, allies, and the private sector.

Secondly, the European Council needs to streamline geoeconomic issues across its work to generate more buy-in from member states. Ministerial meetings, from trade and competitiveness to foreign affairs and economics, deal with geoeconomic aspects largely in isolation. A geoeconomic council that brought these ministers together twice annually would help the European Council to streamline its work. The European Council’s general secretariat must also upgrade its capabilities to support the working groups with relevant analysis. A new service, similar to the legal service, could support streamlining relevant information across different working parties. It could also enhance cooperation on the basis of joint geoeconomic foresight exercises, such as crisis scenarios, to which all relevant working parties contribute and develop preparatory ideas.

Finally, a high-level forum on geoeconomics with public and private participation could support European companies’ geoeconomic vigilance and buy-in for the needed techno-industrial intelligence cooperation. A former head of state could serve as the forum’s head and produce public reports with concrete recommendations on how private and public sectors can enhance their cooperation.

Push for G7 economic security standards

The EU and its allies should develop economic security standards which determine participation in strategic supply chains based on a number of standards other than cost. These could include the resilience, cyber security, sustainability, and trustworthiness of a supplier, defined with detailed thresholds. Priority supply chains should include those which EU and G7 partners have identified as critical – such as AI, biotechnology, quantum computing, and semiconductors – and strategic – such as critical raw materials and clean energy technologies.

Defining economic security standards with G7 allies (a process that has already started) would be the most promising and impactful avenue, as their combined markets represent a powerful lever to shape strategic supply chains. But conversations must include any emerging economies which have stakes and ambitions in these strategic supply chains, such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, or Morocco for clean technologies, on the basis that the standards allow for greater participation, competition, and resilience in these industries. Partners that agree on redefining the principles of strategic supply chains could then deploy economic security instruments which are broadly aligned with their shared objectives. On that common basis, they can develop a more fine-tuned methodology that guides under which circumstances state intervention – from targeted restrictions to subsidies – may follow.

Expand partnerships into techno-industrial alliances

A more geoeconomically savvy EU should integrate its proactive goals, such as building positons of strength in key supply chains, into its external partnerships. To do so, the EU should build economic alliances of partners across entire industrial ecosystems. This approach would help it identify partners that hold assets, such as advanced manufacturing facilities, research and development centres, specialised equipment suppliers, raw material inputs, or useful supply chain linkages, which complement European strengths or fill a gap. A more targeted approach to economic engagement and partners would thereby emerge – similar to what the EU has started with its raw material diplomacy, but expanded along entire supply chains and industrial ecosystems. A battery alliance, for example, could bring together the EU’s sprawling web of mineral partners (such as Argentina, Chile, Norway, and Zambia), technology partners (such as South Korea and Japan), and the EU for its powerful automobile market.

The EU will need to offer concrete ways to coordinate trade and industrial policies for these alliances to be effective. For example, it would need to ensure its financial tools, such as Global Gateway, can support industrial projects in battery alliance countries and that these partner countries have access to financial incentives in Europe, including preferential market access.

From de-risking to re-powering

The EU’s approach to managing geoeconomic developments has started by focusing on risks. It provides a good foundation, but more is needed to bind the different elements of its approach – promote, protect, partner – into a coherent strategy that will enable it to strengthen its geoeconomic position and contend with challenges. The next EU institutional cycle offers an opportunity to develop a proactive approach that thinks beyond immediate risks, build a more geopolitical and less siloed structure, and reassess the traditional principles governing the most critical supply chains.

This cannot happen by focusing on the EU alone. More than ever, Europe’s geoeconomic options are conditioned by the actions of others. The EU cannot achieve a better geoeconomic position without engaging with close allies and partners in new multilateral constellations.

All of this requires a radical change in mindset that focuses on strengthening its position in the global playing field.

About the authors

Tobias Gehrke is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, where he leads the Geoeconomic Strategy Group. He works on geoeconomics, focusing on economic security, European economic strategy, and great power competition in the global economy.

Filip Medunic was the European Power coordinator at the European Council on Foreign Relations from June 2022 until May 2024, and worked on geoeconomics topics with ECFR since 2020. Since June 2024, he is a research fellow for geoeconomics at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), where he focuses on economic security, economic statecraft and German and European foreign and economic policy.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to the numerous policymakers, diplomats, and business representatives with whom we have collaborated in the ECFR Geoeconomic Strategy Group over the past year. Their generosity in sharing their time and ideas in a series of workshops and seminars has been invaluable to this brief, providing us with essential guidance. We also appreciate the contributions of the entire geoeconomics team at ECFR – Agathe Demarais, Alberto Rizzi, and Herman Quarles – as well as many other colleagues from the Asia and Africa programmes to the climate, communications, and advocacy teams for their incredible support across the entire project. Special gratitude is reserved for our editor, Flora Bell, for her unwavering commitment to enhancing this brief. Her many dedicated hours have been a game-changer.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)