Escalating Israel-Iran Tensions in the Middle East

Long-simmering hostilities between Israel and Iran have edged closer to open confrontation. In late 2024 and early 2025, Israeli officials began openly signalling readiness for pre-emptive strikes on Iran’s nuclear and military sites. U.S. intelligence assessments warned that Israel was likely to attempt strikes on Iran’s Fordow and Natanz nuclear facilities in the first half of 2025.

Israel’s defence minister Yisrael Katz hinted in January that upcoming months would present challenges requiring military readiness, citing ongoing threats from Iran and its proxies. This sabre-rattling comes amid tit-for-tatattacks. Iran directly targeted Israel with missiles and drones on multiple occasions in 2024, prompting Israeli retaliation and raising the spectre of a broader war. Both sides have used these exchanges to send strategic messages, Israel demonstrating that it will strike to prevent Iran’s entrenchment or nuclear progress, and Iran signalling that any Israeli attack will be met with an expansive regional response.

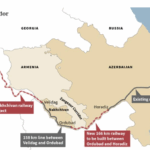

Meanwhile, Iraq finds itself precariously in the middle. Geography places Iraqi airspace between Israel and Iran, making it a potential corridor for military overflights or missile trajectories. Indeed, Iraqi officials complain that their country’s skies have already been used without consent. In one unprecedented incident on October 26, 2024, Israeli warplanes reportedly fired air-launched missiles at Iranian targets while flying through U.S.-controlled Iraqi airspace. Baghdad condemned this “blatant violation” of sovereignty, filing a protest at the United Nations and vowing that Iraq will not allow its airspace or land to be used for attacks on other nations. Despite such assurances, the reality is that Iraq’s ability to enforce that vow is in question, a direct consequence of limited air-defence capabilities and the outsized influence of foreign powers. As Israel and Iran escalate their confrontation, Iraq is increasingly caught in the crossfire, forced to grapple with an air-defence puzzle that has grave implications for its sovereignty and security.

Iran’s Expanding Missile and Drone Network

Iran has spent years hardening and expanding its missile and unmanned drone arsenal across the region, pursuing what it calls an asymmetric deterrent strategy. Tehran has invested heavily in hardened defence infrastructure, including an extensive network of underground missile silos and tunnels colloquially known as missile cities. IRGC commanders boast that there are few cities in Iran that do not have a missile city, with so many underground launch sites that enemies would be unable to effectively counter them. Recent Iranian state media footage showcased a massive subterranean missile basestoring advanced ballistic missiles like the Emad (range ~1,700 km), Qadr (1,800–2,000 km), and Qiam (800–1,000 km). These missiles cover a spectrum of ranges capable of striking targets across the Middle East, from U.S. bases in the Gulf to Israel’s major cities and are increasingly accurate and evasive. Notably, Iran’s Emad and Qadr medium-range missiles can reach Israel and carry substantial payloads, while the Qiam’s solid-fuel design enables quick launches intended to overwhelm or bypass air defences. To protect these strategic weapons, Iran’s military has literally gone underground, storing missiles in fortified tunnels mitigates the risk of Israeli or U.S. pre-emptive strikes and ensures Iran’s ability to retaliate even after an initial attack.

Equally significant is Iran’s prolific drone program and its transfer of missiles and drones to allied militias across the region. Over the past decade, Iran has armed proxy forces in Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq with increasingly sophisticated rocket and missile systems. By 2018, U.S. intelligence concluded Iran had transferred dozens of short-range ballistic missiles, including Zelzal, Fateh-110, and 700-km range Zolfaghar missiles, to militias in Iraq. This effectively turned parts of Iraq into forward launchpads for Iran’s missile force. Indeed, Israeli intelligence detected and reacted to these deployments: in 2019, Israel launched at least seven airstrikes on Iranian-backed militia depots in Iraq to destroy missiles and arms caches. Those strikes, while tactically successful, killed and injured dozens of Iraqis and provoked public outcry over Iraq’s violated sovereignty. They underscored how Iran’s arming of proxies drags Iraq into Iran’s conflict with Israel, making Iraqi soil a potential battleground.

Iran’s use of Iraq as part of its missile network was further evident during the Gaza war spillover in 2024. According to analysts, the number of missiles and drones being fired from Iraq [at Israel] has gone through the roof as Iran leaned on axis of resistance militias to harass Israel. Iran reportedly even utilised Iraqi airspace as a firing corridor: in one large-scale attack in April 2024, Iran launched roughly 300 drones and missiles toward Israel, in retaliation for an IRGC commander’s killing in Syria. All those projectiles flew over Iraq, and some that were not intercepted fell inside Iraq, including a wrecked drone that crash-landed near the holy city of Najaf. Pro-Iranian Iraqi militias also directly launched their own rockets and drones at Israel during this period, in coordination with other Iranian proxies like Yemen’s Houthis. Tehran’s strategy is clear. By dispersing missile and UAV launch sites across multiple neighbouring countries, it can threaten Israel on multiple fronts and complicate Israel’s defensive calculations. However, this expansionist approach also risks making those very neighbours, like Iraq, a “missile corridor” and a target if war erupts. Iraqi leaders are keenly aware of this vulnerability.

Israel’s Pre-emptive Posturing and Air Defence Capabilities

Israel, for its part, has a track record of striking first when it perceives an existential threat, from bombing Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981 to Syria’s Al-Kibar reactor in 2007. Facing Iran’s hardened missile and nuclear program, Israel’s government has stepped up both rhetoric and preparations for possible pre-emptive action. Over late 2024, Israeli forces reportedly rehearsed long-range air strikes, including multi-country drills, and received deliveries of advanced U.S.-made aircraft to boost reach. Israeli officials have openly stressed that they will not tolerate a nuclear-armed Iran, with defence planners reportedly mapping out attack options. Notably, an early 2025 report indicated Israel might strike Iran’s nuclear sites imminently, even if such an attack would only delay Iran’s program by a matter of months. In late October 2024, Israel appears to have already tested Iran’s defences: U.S. intelligence sources say Israeli warplanes launched a covert raid that degraded Iran’s air defences and left Tehran exposed to a follow-on assault. Iranian officials acknowledged that an Israeli attack occurred, missiles struck an Iranian radar site near the border, killing several personnel, though Iran claimed its air defences prevented deeper incursions. This shadowy exchange highlights the high stakes and brinkmanship at play. Each side is probing for weaknesses: Israel looking to punch a hole in Iran’s anti-air systems, and Iran vowing “devastating” retaliation for any major strike.

Should open conflict erupt, both Israel’s offensive capabilities and defensive shield would be put to the test. Israel has built a formidable long-range strike force, including American-supplied F-35I stealth fighters and F-15I strike aircraft, likely to be supported by aerial refuelling and intelligence from the United States. Less openly discussed but equally critical are Israel’s own missile forces, such as the Jericho series of intermediate-range ballistic missiles, which can carry conventional or nuclear warheads and serve as a powerful deterrent against existential threats. On the defensive side, Israel has developed a multi-layered air and missile defence architecture that is among the most advanced in the world. The country’s layered defence approach integrates several systems: Iron Dome batteries to intercept short-range rockets and drones, David’s Sling for medium-range threats, and the long-range Arrow-2 and Arrow-3 interceptors to shoot down ballistic missiles in mid-course or space. In recent confrontations, this shield has been bolstered by U.S. support. For example, during Iran’s massive missile barrage in April 2024, U.S. Patriot missile batteries were deployed in the region (including at least one in Iraq) and American warships contributed SM-3 interceptors from the Mediterranean. Israeli and allied defences managed to destroy or disable most incoming threats in that episode, achieving an interception success rate of roughly 90, 98% according to reports. However, the few projectiles that did slip through, and the sheer scale of Iran’s salvo, illustrate how quickly a full-scale missile war could overwhelm even the best defences. Israeli military planners therefore view neutralising Iran’s launch capabilities at the source as critical. This determination to strike offensively, combined with robust defensive preparations, sets the stage for a volatile dynamic in which split-second decisions could push the conflict across Iraq’s skies.

Iraq’s Airspace: A Vulnerable Corridor

For Iraq, the escalating Israel-Iran conflict presents an agonising scenario. Its airspace could become both a thoroughfare and a battleground for foreign militaries. Iraqi insiders privately warn that if war breaks out, Iraqi lands will be open, as they were in April when all of the missiles crossed Iraqi airspace, referring to Iran’s massive April 2024 strike that used Iraq’s skies as a highway to Israel. Iraq’s government was effectively a bystander as hundreds of Iranian projectiles streaked overhead. Such events starkly demonstrate Baghdad’s limited capacity to control or even monitor high-end military traffic in its own airspace when confronted by determined outside powers. The risk is not only the transit of missiles and jets, but also the spillover of destruction into Iraq itself. In the April 2024 incident, debris and stray munitions landed on Iraqi territory, a harbinger of worse possibilities. Iraqi officials fear that Iran’s use of their country as a missile corridor could invite Israeli pre-emptive action on Iraqi soil. If Iran’s proxy militias in Iraq launch missiles at Israel, Israel might retaliate by striking those launch sites or logistics hubs on Iraqi territory, effectively making Iraq a secondary theatre of the war. Analysts have even speculated that critical Iraqi infrastructure could be targeted in extreme scenarios; for instance, an Asharq Al-Awsat report relayed concerns that Israel might strike Iraq’s Basra port if Iran-backed militias use it to funnel weapons (a comparison drawn to Israel’s strike on Yemen’s Hodeida port following Houthi drone attacks).

Iraq’s government has repeatedly stated its intent to stay neutral in any Israel-Iran conflict, emphasizing that Iraq is in effect a neutral country and will not be a launchpad for aggression. Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani faces the unenviable task of balancing between Tehran and Washington, he must appease powerful Iran-backed factions at home, who have demanded the expulsion of U.S. troops and support Iran’s resistance agenda, while also relying on the U.S.-led coalition for training, counterterrorism, and airspace management support. This tightrope was evident when Iraq filed its UN complaint after the October 2024 Israeli overflight. Baghdad not only condemned Israel but also pointedly raised the issue with Washington, since the U.S. is Tel Aviv’s closest ally and maintains a presence in Iraqi bases that were used in the strike. In response, Iranian-aligned Iraqi militias like Kata’ib Hezbollah have issued thinly veiled threats, warning of a response to this aggression and implicating the U.S. in facilitating Israel’s raid. Those militias have since resumed rocket and drone attacks on American bases in Iraq, after a pause, as if to reinforce that Baghdad cannot easily restrain them. The Iraqi state’s nominal neutrality is thus constantly undercut by non-state actors on its soil that are keen to side openly with Iran. All these factors leave Iraq vulnerable to being drawn deeper into a conflict it does not want, with its airspace, and possibly its territory, serving as a buffer zone where regional powers settle scores.

The State of Iraq’s Air Defence: Legacy Systems and New Initiatives

Iraq’s current air-defence capabilities remain a patchwork of aging assets and nascent upgrades, a puzzle that Baghdad is racing to solve to assert its sovereignty. Decades ago, under Saddam Hussein, Iraq fielded a dense umbrella of Soviet and European surface-to-air missiles (SA-2, SA-3, SA-6, Roland, etc.), but those were largely destroyed or rendered obsolete in the wars of 1991 and 2003. The U.S.-led dismantling of the old Iraqi Army left the country effectively without high-altitude air defences for many years. As a result, since 2003 Iraq has relied heavily on foreign partners to police its skies, especially during the fight against ISIS when coalition aircraft had free rein overhead. Only in the last decade did Baghdad start modestly rebuilding air-defence units. Its initial steps were limited. In 2014, Iraq purchased a handful of Russian Pantsir-S1 short-range gun/missile systems (NATO designation SA-22). Aside from these and some dozens of shoulder-fired Igla (SA-18) MANPADS and old Soviet ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft guns, Iraq’s air defences were mostly rudimentary. This “legacy” arsenal might suffice against terrorist drones or low-tech threats but is woefully inadequate against the kind of high-speed jets, ballistic missiles, and stealthy drones that a potential Iran-Israel war would involve.

Cognisant of these gaps, Iraq has in recent years pursued an accelerated overhaul of its air defence network. The strategy has been to diversify suppliers and acquire medium-to-long-range systems, but this has proven politically tricky. For example, Baghdad showed interest in the Russian S-300/S-400 systems, among the world’s most advanced SAMs, around 2018, even citing the need to protect holy sites from possible aerial terrorist attacks. However, buying major Russian hardware risked triggering U.S. sanctions under CAATSA, as it happened with Turkey’s S-400 purchase, and, after 2022, Russia’s reliability as an arms supplier came into question due to its own war needs. The Ukraine war also disrupted maintenance for Iraq’s existing Russian gear. On the other hand, the U.S. has been hesitant to provide Iraq with top-tier air-defence batteries, like Patriot or THAAD, given Washington’s delicate relations with Baghdad and concerns about Iranian influence in Iraqi institutions. Moreover, Iran-aligned political factions in Iraq vocally oppose any deep military cooperation with the U.S., especially if it involves stationing Western missiles on Iraqi soil. Caught between these poles, Iraq has looked to third options: notably, it quietly inked defence deals with France and South Korea. France has already supplied Iraq with several Thales GM403 long-range air-surveillance radars to improve early warning coverage. French officials have floated offers of short-range Mistral or Crotale SAM systems, and even the medium-range Eurosam SAMP/T (a system comparable to Patriot, capable of intercepting ballistic missiles) as potential sales to Iraq. So far, those talks remain preliminary.

The most significant recent step came in September 2024, when Iraq finalized a $2.6 billion contract to purchase Cheongung II KM-SAM air defence batteries from South Korea. This deal, for eight batteries of the modern medium-range system, is Baghdad’s boldest investment yet in air defence. The KM-SAM, sometimes dubbed the “Korean Patriot”, is designed to intercept both aircraft and ballistic targets, using radar-guided missiles with inertial mid-course updates and active homing in the terminal phase. In essence, it will give Iraq a capability to hit inbound cruise missiles or shorter-range ballistic missiles at medium altitudes, a significant upgrade from the point-defence Pantsirs. Iraqi defence officials indicated that at least two KM-SAM batteries might be delivered quickly, possibly within a year or two, while the rest follow over several years. Baghdad is also seeking to integrate these new systems under a unified command-and-control, presumably with help from partners (for example, by linking French-supplied radar data to the Korean missile units). Still, until these systems are operational, Iraq remains largely exposed. The country has virtually no defence against high-altitude intrusions, as the October 2024 Israeli overflight proved, nor any indigenous ability to shoot down ballistic missiles passing overhead. Even when Iraq’s new SAMs arrive, effectiveness will depend on training and integration. By the time Iraq can field a credible multi-layered air defence, short-range, medium-range, and long-range, the geopolitical landscape may have already shifted.

Notably, Iran has offered its own solutions to Baghdad. A proposal eyed warily in both Washington and some quarters of Iraq’s government. Tehran has pitched its home-grown Bavar-373 long-range air defence system, which Iran claims is on par with the S-400, to Iraq, along with offers of joint Iran-Iraq air defence drills and advisory support. Accepting such assistance would be controversial: it could improve Iraq’s defences on paper, but at the cost of potentially embedding Iranian military personnel on Iraqi soil and deepening Iraq’s dependence on Tehran. U.S. officials have quietly warned that any Iraqi move to host Iranian-operated SAMs would be unacceptable, given the risk to coalition aircraft and the broader political signal it would send. So far, Iraq appears to be holding off on the Iranian offer, preferring to pursue arms deals with non-aligned countries like South Korea and to strengthen its own capabilities without overt alignment. This is emblematic of Iraq’s broader goal which is achieving strategic autonomy in defence by acquiring the effective air defences to secure its airspace without being a pawn in either America’s or Iran’s camp.

Sovereignty and Strategic Autonomy at Stake

The crux of Iraq’s dilemma is how to safeguard its sovereignty amid the looming Israel-Iran clash, while maintaining balanced relations with rival powers. Iraqi leaders often stress that their territory will not be a staging ground for others’ wars. A principle easier stated than enforced. Every incursion into Iraqi airspace, be it an Israeli jet or an Iranian missile, chips away at Baghdad’s credibility and raises domestic pressure for action. The Iraqi government’s protest to the UN over Israel’s October 2024 violation and its high-level complaints to U.S. officials indicate a genuine desire to push back. Yet, sovereignty in the skies ultimately comes from capability. Until Iraq’s air-defence upgrades materialise, it must rely on diplomacy and the goodwill, or restraint, of its neighbours to respect its airspace. So far, that restraint has been in short supply, illustrated by Iran’s own foreign minister touring regional capitals in late 2024 to secure promises that no neighbour would allow attacks on Iran, only for Iran’s military to use a neighbour’s airspace (Iraq’s) days later to launch missiles.

Regionally, Iraq has attempted to play the role of mediator and bridge-builder. In recent years Baghdad hosted multiple rounds of talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia, helping pave the way for their 2023 détente. Iraqi officials have also kept open dialogue with Jordan, the Gulf states, and Turkey, emphasizing that a new regional war would be catastrophic for all. This diplomatic outreach is part of Iraq’s effort to assert a degree of leadership and prevent being relegated to a proxy battlefield. If Iraq can fortify its airspace, even modestly, it might bolster its diplomatic weight by demonstrating it can’t be violated with impunity. However, as things stand, Iraq’s strategic autonomy is constrained. Foreign forces, American and Turkish, operate on its soil, foreign missiles transit its skies, and powerful militias answer more to Tehran than to Baghdad. The Iraqi state’s push to modernise its military, including the air-defence deals with Korea and France, is as much about reestablishing national autonomy as it is about pure defence against jets and missiles. Each radar deployed and each SAM battery procured signals Iraq’s intent to reclaim control of its own domain.

In the interim, Iraqi sovereignty will likely remain somewhat notional in the face of high-end Israel-Iran hostilities. Iraqi airspace is an attractive corridor, relatively undefended and geographically convenient, that either side might exploit. This puts Iraq in an exceedingly precarious position. If Israel strikes Iran via Iraq’s skies again, Iran may hold Baghdad accountable for failing to stop it; if Iran keeps moving missiles through Iraq or allowing its proxies to fire from Iraqi soil, Israel may feel compelled to act within Iraq. Either scenario is a nightmare for Iraqi leaders who want no part of this fight. The coming months will test whether Iraq can accelerate its air-defence preparations and diplomatic efforts enough to avoid being the inadvertent arena for an Israel-Iran showdown. Ultimately, Iraq’s “air-defence puzzle” is about more than military hardware. It is about navigating the intersection of regional power struggles and asserting Iraq’s right to be more than a passive flyover state. The hope in Baghdad is that, through shrewd diplomacy and overdue defence investments, Iraq can reinforce its independence and prevent a larger conflagration from engulfing it. But until those hopes are realised, Iraq remains uncomfortably caught in the crossfire.

By: Muhanad Seloom (PhD)

Assistant Professor, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies

***GEOPOLIST – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics offers diverse viewpoints. The opinions expressed in this text are not necessarily shared by GEOPOLIST.***