The article explores the growing global responsibility of China in addressing conflicts such as those in Ukraine and Gaza. The piece argues that, as a major power, China should play a more active role in promoting peace and stability.

The article highlights China’s diplomatic efforts and its economic influence but emphasizes the need for more decisive action in mediating conflicts and supporting international norms. The article suggests that China’s engagement is crucial in shaping global outcomes and maintaining its international leadership position.

History is mostly made up of the mundane but remembered for the remarkable. For historians of Chinese diplomacy, China’s success in

restoring diplomatic ties between arch-rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia might well be remembered as a turning point. The signing of the

Beijing Declaration for unity by 14 Palestinian factions should have raised eyebrows further – in a most volatile region, China has succeeded in herding the cats, at least for a while.

Can China build on these to become a global peacemaker?

The precondition to being a peacemaker is being trusted for neutrality or, more precisely, impartiality. The neutrality of great powers is not normally very reliable because, given the realism of international relations, self-interest could drive them to alter the distribution of world power in their favour. That is why when it comes to honest brokers, people often think of middle powers such as Norway, Switzerland and Sweden.

But China stands out. Unlike

Britain or

France, it has no historic burden of being a coloniser. Unlike Russia, which would use force to maintain its spheres of influence, China needs no such spheres as its influence, especially in the global economy, is ubiquitous. And unlike the United States, China has shown

no missionary zest to police the world through hegemony or alliance. All of China’s military operations overseas in recent decades, whether in peacekeeping, counterpiracy or disaster relief, have been invariably humanitarian in nature.

If China has waded into deeper waters in the Middle East, then in Ukraine, Beijing has tried its best to strike a balance in a war between two of its friends.

It has almost never voted against or vetoed any of the UN resolutions condemning Russia, but rather only abstained. While the US-led Nato has provided full military support to Ukraine, Beijing has provided no military aid or weapons to Moscow. True, China’s trade with Russia has helped it

skirt Western sanctions, but the trade went on before the war and none of it violates international rules or regimes. Last year, Ukraine’s largest trading partner remained China, with a trade revenue of around US$12.9 billion.

02:02

China skips international peace conference on Ukraine, calls for negotiations ‘as soon as possible’

China skips international peace conference on Ukraine, calls for negotiations ‘as soon as possible’

It remains to be seen how China’s

12-point peace plan and its six-point

joint proposal with Brazil might work. After all, China is not the only country that has tabled a peace plan, and all peace plans rest on the precondition of a ceasefire.

But none is in sight. Russia must gain full control of the

four annexed regions in Eastern Ukraine to be able to declare victory while a Ukraine fully supported by the West has every reason not to relinquish territory.

Still, no war can last forever. As Ukrainian forces lose ground and the US gears up for a presidential election that could

fundamentally change Western support for Ukraine, Kyiv may find it imperative to reach out to Beijing.

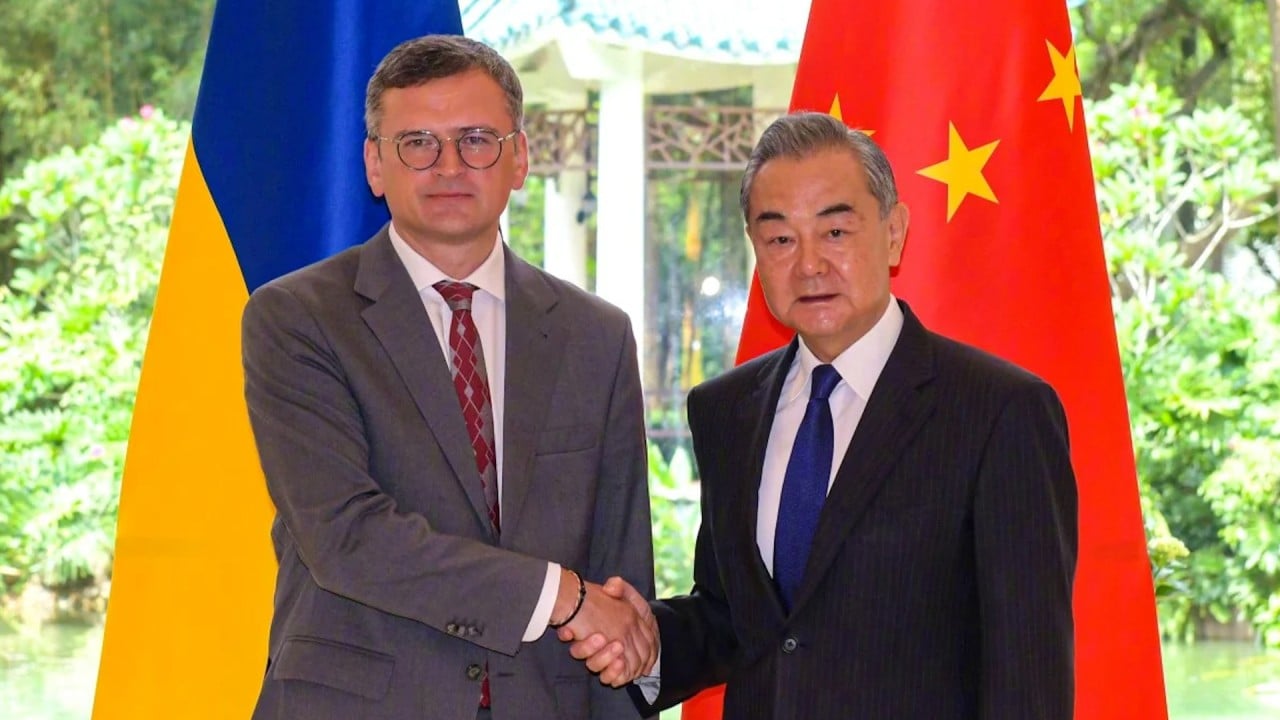

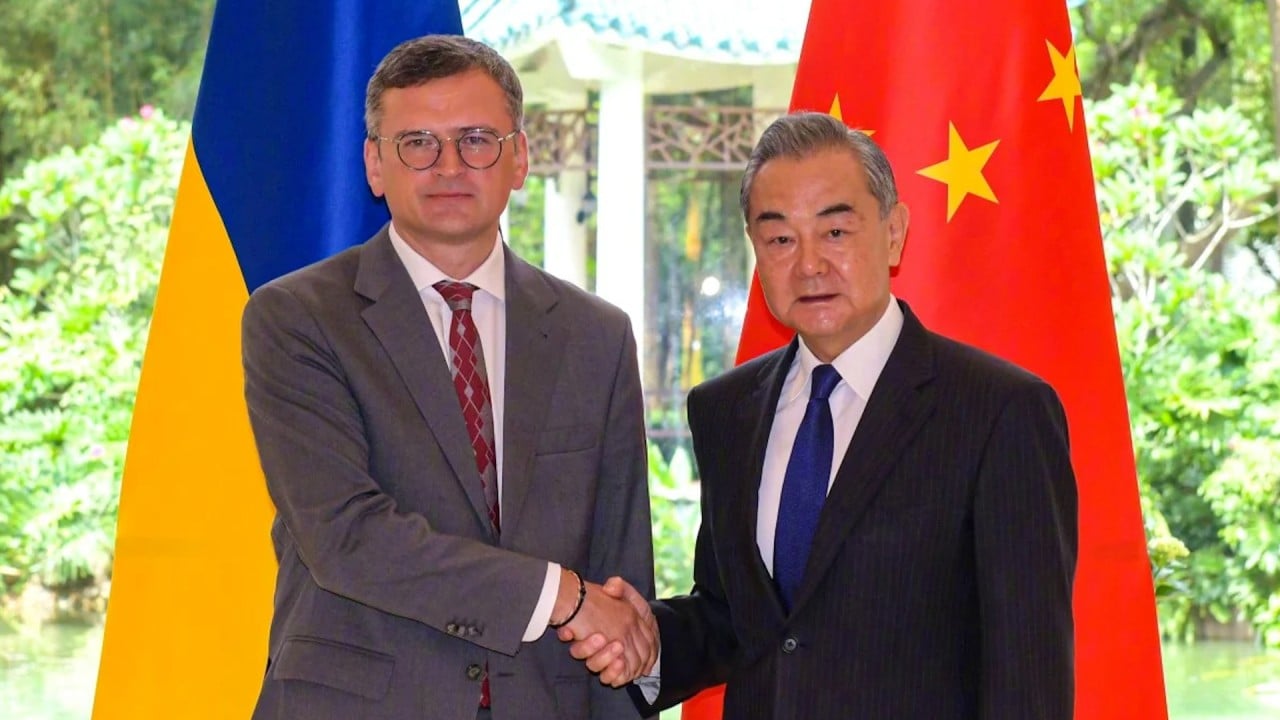

During his first

trip to China since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said “a just peace” in Ukraine is in China’s strategic interests and that Beijing’s role as “a global force for peace” is important.

01:47

Ukraine says it’s ready to resume ‘good faith’ negotiations with Russia

Ukraine says it’s ready to resume ‘good faith’ negotiations with Russia

Beijing can help in at least three ways. First, it can facilitate a ceasefire dialogue between Moscow and Kyiv. Russia was not invited to the

peace summit held in Switzerland in June and China did not attend. Now Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is calling for a second peace summit to be held in a Global South country, and suggested that Russia could be invited. Could that Global South country be China? Should the warring parties agree, Beijing could well be the willing host.

Second, China could, with other major powers, help provide a collective security guarantee for an armistice, the most likely scenario so far after a ceasefire. Without such a guarantee, Ukraine can never be sure that Russia will remain content with what it has annexed, and Russia would worry about the annexed lands becoming another Afghanistan with Ukrainian fighters playing the role of the

1980s mujahideen.

Other questions are bound to crop up. If Ukraine has to give up some of its territory, where will the new border be drawn? Will the contested territory be put under an international trusteeship with proper referendums so residents can state their preferences? Will peacekeeping forces be allowed to monitor ceasefire lines?

None of these issues can be bilaterally resolved by Moscow and Kyiv. They demand United Nations involvement and a large dose of US-China cooperation. If Russia listened to anyone, it would be China. The onus on the US, then, is to secure Ukrainian cooperation.

Third, China is in a better position than any other country to help with post-war rehabilitative reconstruction, be it in Ukraine or Gaza. In March last year, the World Bank estimated the cost of the reconstruction and restoration of Ukraine’s infrastructure at US$411 billion, more than double its 2023 gross domestic product. According to the UN, reconstructing Gaza will need US$40-50 billion at least, with rebuilding lost homes alone taking a minimum of 16 years.

While who will pay for reconstruction in Ukraine and Gaza remains an open question, China’s capabilities in infrastructure-building, which are second to none, can most certainly help.

It is intriguing to see how Beijing is starting to have a say in Europe and the Middle East where it has traditionally pursued economic gains and downplayed any security role. When China started reforms in the late 1970s, it was

“crossing the river by feeling the stones”. It is now wading into the ocean and there is no seabed it can touch nor can it turn back. Being a responsible global power comes at a price.

By: Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) – a senior fellow of the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University