In the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, the city of Sulaymaniyah has once again become the stage for an unprecedented level of conflict between two cousins. From the early hours of the morning, the power struggle erupted into fierce clashes — more akin to a war than an ordinary political dispute. After four hours of fighting, Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) leader Bafel Talabani subdued his cousin, Lahur Sheikh Jangi Talabani, whom he had forced out of the party’s co-chairmanship in 2021.

In the early hours of August 22, 2025, security forces encircled the Lalezar Hotel in the city’s west, where Lahur Sheikh Jangi Talabani had been staying after a court issued a warrant for his arrest the day before. Around 3 a.m., gunfire and explosions shook the streets as clashes broke out, lasting nearly four hours. By dawn, Talabani and his brothers (Polad and Aso) were in custody, with Polad Sheikh Jangi injured during the fighting, according to sources.

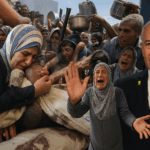

For four hours, the city was gripped by the sound of heavy gunfire, a battle that looked more like a scene from the Kurdish civil war of the 1990s than an ordinary law enforcement operation. What was presented as the enforcement of a judicial warrant in fact revealed itself to be the violent settling of scores within the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the party once synonymous with the late Jalal Talabani.

The crisis began hours before the raid with unusual movements of PUK-affiliated forces on the streets of Sulaymaniyah, triggered by a court ruling that many dismissed as political theater. The Asayish Investigation Court had issued an arrest warrant for Lahur under Article 56 of the Iraqi Penal Code, accusing him of endangering security and destabilizing order. Court spokesman Salah Hassan stated that if charges of attempted coup and undermining security were proven, Lahur could face at least seven years in prison, insisting the decision carried no political motive. Few believed him.

Operating from the upper floor of the Lalezar Hotel, which served as both his residence and command center, Lahur declared: “I am at home. We have done nothing. We have received no formal notice. If they come for us, we will respond.” He refused to surrender and soon issued what sounded like a farewell message:

“I am now on the hotel rooftop. Friends have decided to attack me. This may be my last message to the people of Kurdistan. We are standing firm. We will live standing, and die standing. I chose to stay here and never bow to corrupt political powers. I love you. I love my country. I have proven my Kurdishness. Forgive me if I wronged you. This may be my last message.”

His brother Aras Sheikh Jangi warned that 400–500 well-trained and armed men were positioned nearby, predicting inevitable casualties. At 3:00 a.m., the clashes erupted. Buildings were damaged, cars burned, and firefights spread through the streets until Lahur and his brothers were overpowered. At least 48 fighters from Lahur’s loyalist force, known as Dupishk, were detained, including their commander Hamid Haji. Reports put the total number of combatants at around 70–80. By morning, seven of Lahur’s men and three security personnel had been killed, and 10–15 more were wounded.

The fog of war also produced unconfirmed reports that Bafel Talabani’s residence in Dabashan had been hit by a drone strike, sparking a fire. Adding to the irony, the Counterterrorism Unit, once commanded by Lahur himself, joined the operation against him. After the clashes, the court announced a new murder investigation targeting Lahur and his men. Local sources suggested that Lahur, Polad, and their families would be exiled to Sweden, while Aras would be sent to the UK. The purge, insiders warned, could extend further, ensnaring senior PUK figures such as Mala Bakhtiyar and former Iraqi president Barham Salih.

At first glance, the episode might appear as nothing more than a family quarrel between cousins — Lahur and Bafel Talabani, the current PUK leader. Yet such a reading misses the wider significance. The confrontation is best understood as the intersection of three overlapping crises: the long-term fragmentation of Kurdish politics, the accelerating closure of democratic space in the Kurdistan Region, and the intensifying regional contest among Turkey, Iran, and other regional actors, including the US and Israel.

The Roots of the Feud

The story of the feud has its roots in the death of Jalal Talabani– the father of Bafel and uncle of Lahur, whose towering presence once held the PUK together. In the years that followed, the party leadership sought a formula to preserve unity while preventing any one faction from dominating. At the PUK’s 4th Congress in 2019, Lahur Sheikh Jangi emerged as the clear winner, securing 902 votes to his cousin Bafel’s 791. His popularity, especially among younger cadres and grassroots members, alarmed those in the Talabani family who feared that Jalal’s legacy could slip from their control. Rather than allow Lahur to claim the position of general secretary, the office was abolished altogether. In its place, the leadership engineered a compromise: the introduction of a co-chairmanship system, pairing Lahur with Bafel in 2020. The arrangement was fragile from the outset, an uneasy truce between two cousins who represented not just personal rivalries but competing networks of power, patronage, and external alliances. Within a year, the experiment collapsed, with Bafel moving decisively to consolidate control and push Lahur aside in what was described at the time as a “bloodless coup.” Lahur was accused of corruption, abuses of power, and even of plotting to poison his cousin. He refused, however, to retreat from politics.

With deep ties to the intelligence and counterterrorism apparatus of the Kurdish security state, and with loyal followers still under arms, Lahur remained a force to be reckoned with. His decision to launch the People’s Front (Bêrêy Gel) in early 2024, which secured seats in the Kurdistan Parliament, gave him an institutional platform as well as a symbolic one. For Bafel, who had consolidated control of the PUK, this was intolerable: Sulaymaniyah, long the Talabani stronghold, could not be allowed to host an alternative center of power.

The raid of August 22 was therefore not simply about enforcing a warrant. Officially, Lahur was accused under provisions of the Iraqi Penal Code ranging from “disrupting security and stability” to “premeditated murder.” Yet the intensity of the operation — with tanks rolling through Sulaymaniyah’s streets and drones circling overhead — exposed its true purpose: the physical destruction of a rival’s base of power. That message was reinforced by the arrests of Lahur’s brothers and his senior commander, Rebwar Hemid Haci Xali.

This assault also fits into a broader campaign. Just ten days earlier, on August 12, security forces had arrested Shaswar Abdulwahid, the leader of the New Generation Movement, a reformist party that had challenged both the PUK and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Two opposition leaders taken off the field in less than two weeks cannot be coincidental. Together they signal the closing of political space in the Kurdistan Region, a retreat from even the limited pluralism that had once distinguished Sulaymaniyah as a hub of debate and dissent. What is unfolding is the reassertion of the old two-party duopoly — the Barzanis in Erbil, the Talabanis in Sulaymaniyah — with rivals either absorbed or eliminated.

The Shadow of the 1994–1998 Kurdish Civil War

To understand why the arrest of Lahur Sheikh Jangi has generated such alarm, it is necessary to revisit the history of Kurdish internal conflict. The most dramatic episode remains the Kurdish civil war of 1994–1998, in which the PUK and the KDP fought a fratricidal conflict that left thousands dead and displaced and nearly shattered the experiment in Kurdish autonomy established after the Gulf War.

At its heart, the conflict was about territory, patronage, and external alignment. The PUK controlled Sulaymaniyah, Halabja, and parts of Kirkuk; the KDP dominated Erbil and Dohuk. Both sought to control the flow of revenues — especially from customs checkpoints and smuggling routes to Turkey and Iran. As the war dragged on, both parties called in outsiders. The PUK leaned heavily on Iran, while the KDP struck deals with Turkey and, notoriously, with Saddam Hussein, whose tanks rolled into Erbil in 1996 at Masoud Barzani’s invitation.

The war ended only after U.S. mediation led to the Washington Agreement of 1998, which froze territorial lines and enshrined a two-party system of governance in the Kurdistan Region. That duopoly has never really loosened its grip. Every attempt to break it — from the hopeful rise of Gorran in the late 2000s to Lahur Sheikh Jangi’s People’s Front in 2024 — has been met with the same blunt response: repression, co-optation, or open violence. The clashes in Sulaymaniyah last night did not come out of nowhere; they were simply the latest chapter in a familiar cycle. In Kurdistan, challengers rise, hope flickers, and then the old guard smothers it before it can take root.

The Rise and Fall of Gorran

The boldest challenge came with the Change Movement, or Gorran, launched by Nawshirwan Mustafa in 2009. Mustafa was no stranger to the game. A onetime PUK commander and a sharp political thinker, he had spent a lifetime navigating the shadows of Kurdish power. He knew its rituals, its betrayals, its bargains. Yet when he finally struck out on his own, the vision he offered was almost disarmingly simple: end corruption, open the books, and make leaders answer for their actions.

For Kurds long suffocated by warlord politics, backroom deals, and the endless recycling of family dynasties, that message landed like fresh air after a storm. In 2009, it turned into a movement. Gorran — “Change” — swept into parliament with 25 seats, jolting the old order. Suddenly, here was an opposition that belonged to neither the KDP nor the PUK, a force that spoke the language of the street rather than the language of patronage. For a moment, hope felt real. Kurdish politics seemed ready to breathe differently.

But hope rarely lasts long in Kurdistan. The system hit back, hard. The KDP wielded its grip on the presidency and its iron control of the security services to shut every door Gorran tried to open. The PUK, threatened by Mustafa’s charisma and networks, worked to co-opt or sideline his rising protégés. And inside Gorran itself, fault lines opened: reformists against pragmatists, dreamers against dealmakers.

When Nawshirwan Mustafa died in 2017, it wasn’t just the loss of a leader — it was the shattering of a spine. He had been the glue, the anchor, the soul of the movement. Without him, Gorran drifted into infighting, its fire dimming year by year. By the 2020s, what once looked like a revolution had withered into irrelevance. The “Change” movement that had promised to topple the duopoly was quietly folded back into it, becoming part of the very system it had sworn to undo.

The PKK–Turkey Conflict and Sulaymaniyah’s Role

Another shadow over Sulaymaniyah is the conflict between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). For Ankara, Sulaymaniyah has long been viewed as a sanctuary for PKK cadres and sympathizers. Unlike Erbil, which is firmly under KDP control and closely aligned with Turkey, Sulaymaniyah has often been more permissive toward groups opposed to Ankara’s policies.

Lahur Sheikh Jangi was particularly vocal in opposing Turkish military incursions. He criticized Ankara’s growing presence in the Kurdistan Region and openly supported Kurdish forces in northern Syria (Rojava). In 2021, he accused President Erdoğan of personally ordering his assassination, even suggesting that Turkish missiles had been aimed at him. Such rhetoric ensured that Lahur was viewed in Ankara as not just a political rival but a security threat.

This helps explain Turkey’s rapid response to the events of August 22, 2025. Although Ankara expressed “concern” for stability, it likely welcomed Lahur’s removal. From Ankara’s perspective, a PUK firmly under Bafel’s leadership is preferable to one divided by a cousin who openly opposes Turkish interests. Yet Turkey’s satisfaction may be short-lived. The weakening of the PUK also strengthens the KDP, which already dominates relations with Ankara. An overly weakened Sulaymaniyah may upset the balance of power that has long stabilized the Kurdistan Region.

The U.S. Role Since 2003

The United States has played a decisive role in shaping Kurdish politics since the 2003 invasion of Iraq. American forces relied heavily on Kurdish militias during the war and later cultivated deep ties with Kurdish security institutions. The Counter-Terrorism Group (CTG), co-founded by Lahur and Bafel in 2002 with U.S. backing, was one of the most important instruments of this cooperation.

During the war against the Islamic State, Lahur’s forces became indispensable. They fought alongside U.S. Special Forces in operations across Kirkuk, Diyala, and Makhmur. American commanders frequently praised Lahur’s professionalism and reliability. Yet the U.S. relationship with the Kurds has always been transactional. Washington has tended to view Kurdish leaders as partners in counterterrorism but has shown little interest in protecting them from internal repression.

The U.S. Embassy in Baghdad issued only a muted call for restraint. This reflects both the narrowing of U.S. leverage and a reluctance to intervene in Kurdish internal politics. But the perception of abandonment could have lasting consequences. Future Kurdish leaders may hesitate to invest in cooperation with Washington if they believe it leads only to later vulnerability. The muted American response to Lahur’s arrest — a bland call for restraint — reflects this pattern.

Iran and the Politics of Sulaymaniyah

No discussion of Sulaymaniyah is complete without considering Iran’s role. Tehran has long cultivated networks within the PUK, providing financial, political, and military support. During the 1980s, when Jalal Talabani led the PUK in opposition to Saddam Hussein, Iran was his principal backer. After 2003, Tehran continued to cultivate influence, particularly in Sulaymaniyah, which lies close to the Iranian border and serves as a corridor for trade, intelligence, and proxy activity.

Lahur’s perceived closeness to Western intelligence always made him suspect in Iranian eyes. Some in Tehran accused him of facilitating U.S. operations that led to the assassination of Qassem Soleimani in Baghdad in 2020. His removal from the PUK leadership in 2021 and his arrest the other day both align with Iran’s preference for a compliant PUK under Bafel’s leadership. At the same time, Iran faces risks. An overly weakened PUK could destabilize Sulaymaniyah, creating opportunities for rivals, including Turkey, the United States and even Israel, to expand their influence.

The Kurdish Opposition Question

The arrest of Lahur and the suppression of Abdulwahid raise important questions about the future of the Kurdish opposition. The Kurdistan Region has often been described as a model of stability in Iraq; however, this stability is built on an oligarchic foundation. While elections are conducted, real power rarely shifts. Since the 1990s, a two-party system has prevailed, with the Barzani-led KDP and the Talabani-led PUK sharing control over territory, resources, and institutions.

Opposition parties, from Gorran to New Generation, have challenged this arrangement, but their fate has been consistent: they are either absorbed, marginalized, or eliminated. Lahur’s arrest is therefore not only about one man or one faction. It is about the continued refusal of the Kurdish political establishment to tolerate meaningful pluralism. If this pattern continues, the risks of renewed unrest, disillusionment, and even armed resistance will grow.

Strategic Forecast: Three Scenarios

The first possible future is one of authoritarian consolidation. In this path, Bafel and the Barzanis tighten their grip, silencing rivals and hollowing out the meaning of elections. The forms of democracy remain — ballots, campaigns, official ceremonies — but the substance is gone. Order is maintained, but at the steep cost of freedom.

The second trajectory is far darker: a relapse into civil conflict. As Sulaymaniyah’s political space closes, opposition voices may see no outlet but force. If Lahur’s loyalists regroup, the city could again echo with the gunfire and bitterness of the 1990s, when intra-Kurdish war tore at the fabric of society. Such unrest would not stay contained. Turkey and Iran would quickly revive old habits of arming rival factions, and while the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) might first welcome a weakened Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the spiral would soon prove dangerous for all. Violence spreading beyond Sulaymaniyah could destabilize Erbil, draw Baghdad into the fighting, and tip the whole of Iraq into crisis.

The third, best-case scenario is fragile pluralism. Here, pressure from abroad could matter. If international actors push for reforms, defend civic space, and support genuine political competition, Kurdistan could preserve at least a measure of pluralism. It would not be full democracy, but it could protect a breathing space where voices of dissent still survive.

Taken together, the Talabani vs. Talabani showdown is far more than a family feud. It is a mirror of Kurdish politics at its breaking point: the drift toward authoritarianism, the shrinking room for democratic life, and the deepening dependence on outside powers. The violent spectacle in Sulaymaniyah was not just about who controls a hotel or a party headquarters. It was a warning — that the very experiment of Kurdish self-rule, once hailed as a beacon in a turbulent region, now risks collapsing under the weight of its contradictions.

History shows this pattern is not new. From the civil war of the 1990s to the suppression of Gorran, Kurdish politics has repeatedly swung between moments of pluralist opening and cycles of oligarchic retrenchment. The Lahur episode is the latest reminder that this cycle remains unbroken.

The stakes today are far higher. What begins as a power struggle in Sulaymaniyah could spill across the Kurdistan Region and, eventually, engulf Iraq as a whole, with regional powers poised to exploit the turmoil.

By: GEOPOLIST – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics