The run-up to the 2024 Iranian presidential election is marked by significant internal challenges. These include recent events such as the parliamentary elections in March 2024, a prolonged economic downturn, repeated social unrest, and tense relations with Israel.

The political landscape is preparing for a crucial election, but the internal workings of Iran’s political system remain complex and sometimes unclear. This article aims to shed light on the hybrid nature of the electoral process and the key points of the six candidates’ programs. However, it is important to note that the impact of elections on Iran’s strategic direction remains limited, as decision-making power ultimately rests with the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei.

The presidential election takes place in a tense climate

The Iranian presidential election is scheduled for June 28, 2024. This date has been determined in accordance with Article 131 of the Iranian Constitution, which mandates that an election must be held within 50 days after the death of the president.

Ebrahim Raissi, the president, and Hossein Amir Abdollahian, the foreign minister, tragically lost their lives in a helicopter crash near Azerbaijan on May 19. Vice President Mohammad Mokhber now serves as the acting president.

The death of President Raissi has significantly impacted Iranian society, which is already grappling with political, economic, security, and social instability. The unprecedented low voter turnout in the March 2024 parliamentary elections has once again allowed the ultraconservatives to maintain control of the parliament (Majles). However, this control is based on fragile popular legitimacy, as shown by the low turnout and the high number of blank votes.

The economic situation in Iran is critical. Inflation remains high at 40%, unemployment is on the rise (8.6%), and the value of the Iranian rial continues to depreciate.

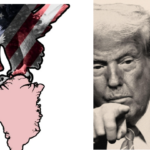

The Iranian morality police have become increasingly brutal towards Iranian women, enforcing strict hijab rules. Relations between Iran and Israel remain tense, with tensions escalating after the strikes on their respective territories in April. While the Iranian regime appears to avoid direct conflict with Tel Aviv, aware of its fragile position in the face of growing internal tensions, Tehran remains determined to pursue its regional ambitions and maintain a posture of strategic defiance towards Israel.

Recently, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom issued a joint statement condemning Iran’s measures to increase its nuclear capacity at the Natanz and Fordow power stations.

The presidential election in mid-June takes place against a backdrop of growing uncertainty and critical issues at both the national and international levels.

The Guardian Council: a hybrid body at the heart of a two-headed system

The institutional framework in Iran is complex and unique, as two authorities coexist: a democratic one and a theocratic one.

The democratic legitimacy of the country comes from popular suffrage, which is exercised through general elections. These elections allow citizens to choose their representatives, including the President of the Republic.

On the other hand, theocratic legitimacy is represented by the Supreme Leader, who oversees all institutions in the country, including the Council of Guardians of the Constitution.

The Council of Guardians consists of twelve members who serve six-year terms. Six members are appointed by the Supreme Leader, while the other six are selected by members of the Majles (the Iranian parliament).

The Council of Guardians plays a crucial role in the electoral process. It is responsible for validating presidential candidates before the elections, monitoring the voting process, and approving or rejecting the final results of the ballots. This prerogative gives religious authorities the power to ensure that only candidates who conform to Islamic principles are allowed to stand for election.

The influence of religious power on the selection and approval of presidential candidates reveals the dynamics of Iran’s two-headed system. This interaction between religious institutions and the electoral process highlights the duality of power in Iran, which affects democracy and political representativeness.

The challenges of early elections: political, economic and social perspectives

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, various individuals have led the Iranian regime, representing both conservative and reformist viewpoints. The early elections on June 28th saw 80 candidates, including four women, compete for the position. Only six of them were approved by the Guardian Council.

One of the key themes in the candidates’programs is managing international sanctions. Alireza Zakani, an ultraconservative mayor of Tehran, supports self-sufficiency and advocates for de-dollarization. He argues that Iran must become independent to gain international respect.

On the other hand, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, a conservative candidate and chairman of the Majles with experience in the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution (Pasdaran), suggests diplomatic efforts to lift sanctions gradually. He believes that the Sino-Iranian relationship offers alternative ways for Iran to develop its economy and mitigate the impact of sanctions.

The economy is a central focus in the candidates’ proposals. Masoud Pezeshkian, a senior parliamentarian and the only reformist candidate, highlights internal corruption and stresses the importance of adhering to global financial standards set by the FATF to attract foreign investment.

Mostafa Pourmohammadi, a former justice minister and the only cleric in the race, argues that the 29% interest rates charged by banks are responsible for inflation in Iran. To better control inflation, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf advocates for greater independence from the central bank. He also emphasizes the need for greater cooperation with international organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Council and BRICS, of which Iran has been a member since January 2024.

Another important issue discussed by all candidates is the status of women and the hijab. Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf supports gender justice rather than gender equality, highlighting the central role of women in the family sphere.

Masoud Pezeshkian, on the other hand, is opposed to any form of coercion to impose the hijab. Saeed Jalili, a former Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council and Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator between 2007 and 2013, criticizes Western models and highlights the success of veiled Iranian women as a powerful alternative model.

Ghazizadeh Hashemi, the director of the Martyrs Foundation since 2021, focuses on discrimination and inequality of opportunity rather than the hijab. He calls for reforms to better integrate women into the labor market and combat structural discrimination.

Recent Iranian polls predict a close race between the conservative Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, the reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, and the ultraconservative Saeed Jalili. However, the impact of the presidential election on Iran’s strategic direction is likely to be marginal. Politically and institutionally, Tehran’s strategic trajectory is unlikely to undergo major transformations.

By Julia Tomasso, Research Assistant at IRIS

Source: French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs (IRIS)