With President Biden signalling that Ukraine will likely not become a NATO member while the confrontation with Russia continues, the US will need to take the lead at the upcoming Washington NATO Summit in setting out how a new European security architecture beyond NATO can be developed to deter Russia from future aggression and to defend Ukraine in the long term.

Speaking as preparations for the Washington NATO summit on 4–5 July are being finalised, President Joe Biden has indicated in public what the US has been signalling privately for over a year. The White House is not prepared to advance Ukrainian NATO membership if this will risk a direct war with Russia. The way forward for European security in what is set to be a prolonged confrontation with Moscow will therefore likely involve Ukraine as a partner of the alliance rather than a member.

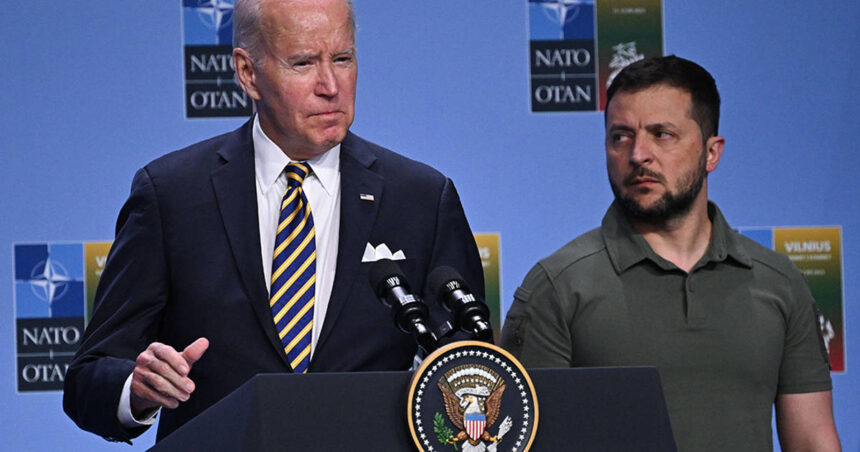

US resistance to Ukrainian NATO membership was already apparent in the summer of 2023. At the July Vilnius summit, the alliance faced one of its most uncomfortable gatherings in recent decades as Kyiv’s expectations of being offered a clear path to membership, cheered on by some European member states, clashed with the reality of US (and German) red lines on enlargement to Ukraine. The summit communique stated simply that ‘Ukraine’s future is in NATO … when Allies agree and conditions are met’. Critical public comments by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the US position at the time caused considerable anger in the White House, leaving a shadow over his relationship with Biden ever since.

To avoid a repeat of the political tensions of Vilnius, ahead of Washington, the US has been attempting to manage Ukrainian expectations by making clear that Washington will not be a membership summit. In recent weeks it has, however, become clear that the current US approach to keeping a firewall between NATO – including on the question of Ukrainian membership – and the war with Russia faces a growing challenge. The Biden administration is concerned that there is a creeping ‘NATOisation of Ukraine’ and of the war.

With Ukraine facing a substantial Russian counterattack, Washington has come under pressure not just from Kyiv but from numerous European capitals to relent on its prohibition on the use of US weapons inside Russia. France and others have been openly discussing the deployment of their troops to Ukraine, raising risks of an expansion of the war. Others have been pushing for the Washington Summit to signal a direct role for NATO in managing assistance to Ukraine. Pressure around the issue of membership has begun to build again, including from the NATO Secretary General. The idea that a ‘NATO invitation’ to Ukraine could be extended in Washington has been floated, only to be dismissed by the US.

To date, the US has successfully managed the alliance in response to the Ukraine war by taking the lead early on in supporting Kyiv and by working diplomatically to forge a broad international coalition to pursue that goal. As the fighting has dragged on, divergent views on how to prosecute the war and how to respond to the Russian threat have begun to emerge. European allies have been pushing the boundaries of NATO involvement in the war, raising concerns in Washington that the alliance risks being drawn into a direct military confrontation with Russia. Biden has concluded that to head off another political fight over membership at the Washington summit, when the US could again be isolated, he needs to make clear that NATO mission creep over the war will not happen.

Biden’s comments will likely be a shock to many and a huge disappointment to Ukraine and eastern-flank NATO states. This is a perilous moment for NATO. It is a reminder of the geopolitical realities of an alliance that continues to rest on US military power and its extended nuclear deterrence, and which is guided by Washington’s interests. The White House position makes clear who will ultimately determine the direction of NATO and how the security relationship with Russia is managed, including the escalation risks around Ukraine.

In recent weeks it has become clear that the current US approach to keeping a firewall between NATO – including on the question of Ukrainian membership – and the war with Russia faces a growing challenge

This will be a hard message to swallow for many who have positioned themselves as cheerleaders for early Ukrainian NATO membership. Critically, it will mean that the White House will need to set out at the Washington Summit a convincing pathway for Ukraine to deter future Russian aggression, to be able to defend itself in the event of an attack, and at the same time to build stronger ties with the Euro-Atlantic community, all in the absence of NATO Article 5 protection. Fortunately, the foundations of such an arrangement have already been put in place.

The Vilnius G7 security commitments framework, agreed on the margins of the 2023 NATO summit, involves over 30 states concluding bilateral security agreements with Ukraine. The declaration indicates that the intention is to formalise ‘enduring support to Ukraine as it defends its sovereignty and territorial integrity, rebuilds its economy, protects its citizens, and pursues integration into the Euro-Atlantic community’. The UK concluded the first such agreement in January 2024. This has been followed by similar agreements with Germany, France, Italy and other states. The US will announce its own bilateral agreement shortly. Other agreements, including with the EU and NATO itself, will be concluded around the Washington Summit.

The Vilnius framework does not offer security guarantees. Equally, it is not the same as the infamous Budapest Memorandum concluded between the US, the UK, France and Russia, which provided Ukraine with security assurances in exchange for Kyiv surrendering its nuclear arsenal in the 1990s. The current set of bilateral agreements are intended to ensure long-term (most agreements are designed for 10 years) and predictable support and a comprehensive security approach to Ukraine.

On the military side, in addition to commitments to supply weapons, the agreements involve expanded training, intelligence sharing, cooperation on cyber and on the protection of critical national infrastructure, and support to develop interoperability with NATO and to build Ukrainian forces according to NATO standards. Woven into the agreements is the formation of capability coalitions to help Ukraine develop more coherent and modernised armed forces. The agreements also contain provisions on economic support, energy security, humanitarian cooperation, assistance with domestic reforms and reconstruction, and sanctions.

While the Vilnius framework offers a clear advance on the Budapest Memorandum, more will need to be done to address the shortcomings of the current arrangements and to convince sceptics that this approach is realistic. At the NATO summit, the US and other allied countries will need to demonstrate their commitment to the bilateral security agreements as a viable and enduring means of protecting Ukraine, but more than this, they will need to set out a path to develop these agreements in order to ensure Ukraine’s future security. Five areas will require further work:

Governance: Ultimately, over 30 separate bilateral agreements are envisaged with Ukraine. This is unwieldy, and an arrangement to strengthen coordination will be needed. Critically, US leadership to ensure the implementation and strategic development of Ukrainian assistance through the agreements will be required. The NATO-Ukraine Council (NUC) would be one possible venue for the collective discussion of the Vilnius commitments. If this comes too close to NATOising the agreements, a standing group under the G7 could be established.

Although the 2023 Vilnius framework offers a clear advance on the Budapest Memorandum, more will need to be done to address the shortcomings of the current arrangements and to convince sceptics that the approach is realistic

Strengthening Political Commitments: The bilateral agreements are political commitments. These go beyond the Budapest Memorandum, but remain ultimately at the mercy of political support within each of the countries. France alone has held a (non-binding) parliamentary vote on its agreement. While it is unlikely that the agreements will become treaties, wider involvement of parliaments (especially the US Congress) would strengthen the political commitment and hold governments accountable domestically for the delivery of support.

Cooperation in the Event of an Armed Attack: Each of the agreements contains provisions for a response in the event of a future Russian attack on Ukraine, including security assistance, military equipment, and economic assistance and sanctions. These provisions go considerably beyond the Budapest Memorandum and approach a sort of ‘NATO article 4.5’ in scope. More, however, could be done to develop these provisions as a deterrence framework, for example by spelling out the steps that would be taken (as part of an escalation ladder) in response to Russian intimidation or a military build-up. These responses should also be coordinated across the set of bilateral security partners to avoid a piecemeal approach – ideally through the governance mechanism identified above.

Developing A Ukrainian Future Force: To deter and defend against future attack, Ukraine will need a military that has a significant advantage over Russian forces. The current bilateral agreements offer a mishmash of national commitments to provide military support, with some coordination through the capability coalitions. Exactly what a Ukrainian future force capable of deterring Russia will need to look like should be agreed among the bilateral supporters, and the set of agreements then coordinated to ensure the successful creation of such a force in the years ahead.

Building Common Euro-Atlantic Deterrence: As a partner rather than a member of NATO, Ukraine will be a security spoke to the alliance hub. This risks leaving deterrence to Ukraine alone. There is, however, scope for future deterrence toward Russia to be better coordinated between NATO and Ukraine – possibly through the NUC. For example, a forward-leaning NATO deterrence posture in the north in times of Russia–Ukraine tensions would weaken Moscow’s ability to concentrate its forces against Ukraine.

The Vilnius framework is not an alternative to Ukraine joining NATO – and the open-door policy begun at the Bucharest Summit in 2008 remains in force. Rather, it can operate as a bridge to eventual membership. However, given that Russian hostility towards Ukraine and confrontation with NATO will likely continue for years to come, even if some sort of political settlement of the war in Ukraine is reached, this bridge is likely to be a long one. In the interim, a clear and strong signal from the US and other allies at the Washington Summit of their enduring commitment to the Vilnius framework and its further elaboration will be vital to reassuring Kyiv and alliance members that Biden continues to see the West’s duty as being to support the defence of Ukraine.

Dr Neil Melvin

Source: Royal United Services Institute (RUSI)