In Turkey, an odd unanimity has settled in: from Erdoğanists to segments of the secular left, people speak about the Gülen movement through the language of crime—but rarely through the language of punishment. The accusation may change in tone (“terror,” “infiltration,” “cult,” “parallel state”), yet the deeper consensus holds: whatever happened, the collective penalties that followed are treated as self-explanatory—asset seizures, mass professional bans and purges, institutional liquidations, and a social “curse” that spreads far beyond any court verdict. What’s missing is the uncomfortable question a society asks when it is still inside the rule-of-law horizon: Even if you believe guilt exists—what kind of punishment is legitimate, and against whom?

That moral blind spot matters, because it’s precisely the kind of blind spot that—historically—has produced something else: a disciplined, economically adaptive, institution-building religious diaspora that eventually looks less like the caricature its persecutors created and more like an unexpected reform current. In this regard, what is emerging among Gülenists in the West is a Calvinist moment inside contemporary Islam: not a theological conversion to Protestant doctrine, obviously, but a diaspora-driven reformation of practice—work ethic, sobriety, civic integration, institutional durability, and (crucially) a shift from leader-centered loyalty toward principle-and-rule-centered survival.

The analogy is not ours alone. Long before the 2016 rupture, researchers were already describing a “Protestant work ethic” dynamic among pious Turkish business circles—so much so that a well-known report popularized the label “Islamic Calvinists,” capturing the blend of religiosity, discipline, and market success in Anatolia. What changed after 2016 is that the Gülen movement—once deeply entangled in Turkey’s power struggles—was thrown into exile en masse, and exile has a way of forcing movements to choose: either become a permanently resentful sect, or learn to live by institutions, law, and long-term civic credibility.

Defining “Calvinist Islamism”

At its core, Calvinist Islamism is a conceptual framework describing Islamist activism that mirrors the qualities Max Weber attributed to ascetic Protestantism: diligence, discipline, and worldly engagement in service of faith. Rather than revolutionary zeal or personality cults, these Islamist actors emphasize education, entrepreneurship, and community institutions – much like Calvinists valued schools, guilds, and self-governing congregations. Analysts have in fact dubbed some of Turkey’s pious entrepreneurs and community-builders “Islamic Calvinists,” noting their own frequent attribution of success to a “Protestant ethic.” In the mid-2000s, for example, researchers observed a “quiet Islamic reformation” among Anatolian Muslim entrepreneurs and titled their study “Islamic Calvinists,” highlighting the fusion of Islamic values with practical rationality in free-market enterprise. A number of these “Islamic Calvinists” were followers of Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen, whose movement became renowned for business success and funding of schools. In other words, long before the term “Calvinist Islamism” was coined, the hallmarks of the idea were visible: devout Muslims coupling hard work, frugality, and education with religious purpose – an Islamic analogue to the Calvinist work ethic that even critics acknowledge.

Equally important is the mode of leadership and authority in such movements. Principle-based leadership – grounded in doctrinal values and institutional norms – takes precedence over charismatic authority. This contrasts with more personality-driven Islamist currents led by singular figures or firebrands. In “Calvinist Islamist” circles, the legitimacy of leaders flows from their ability to embody and implement shared principles (such as service, honesty, or consultative decision-making) rather than populist charisma. For instance, Fethullah Gülen himself has been described as a pragmatic, principle-focused leader who “provides inspiration, motivation, vision, and overarching principles” to his followers, without an overt cult of personality or formal hierarchy. Observers like scholar Hakan Yavuz have even likened Gülen’s ideas to Calvinism in their encouragement of neoliberal entrepreneurship and self-discipline. The broader pattern is that these movements seek to routinize their values into durable institutions (schools, charities, civic organizations) which outlast any one leader. Authority is often decentralized or exercised through boards and councils, echoing how Calvinist churches were governed by elders and presbyteries rather than by bishops or singular holy men.

Gülen Movement in Western Diasporas After 2016

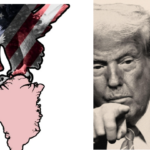

The 2016 coup attempt in Turkey and its aftermath set the stage for a dramatic manifestation of this trend. The Turkish government’s purge of the suspected orchestrators – primarily the Gülen movement (dubbed FETÖ by Ankara) – led to the mass exile of tens of thousands of Gülen-affiliated individuals.

In both cases—French Calvinists (Huguenots) and the Gülen movement—opponents built a politically powerful narrative of “office capture”: the idea that a tightly knit religious network quietly promotes its own members, protects insiders, and turns state institutions into an extension of the community. In early modern France, this suspicion attached itself to Huguenot organizational cohesion—synods, assemblies, and dense patronage ties—and critics often portrayed Protestants as a “state within a state,” implying that any Protestant presence in sensitive offices would translate into confessional favoritism. Even where Protestants served the crown in ordinary ways, their solidarity could be reinterpreted as illicit factionalism: a claim that “they look after their own” and bend justice or administration toward co-religionists rather than the crown’s neutral order.

The modern version of the same accusation was directed at the Gülen movement in Turkey, but expressed in bureaucratic language: cadre-placement in the police, judiciary, and military; preferential recruitment through recommendation chains; and, at the most extreme end of the allegation spectrum, the claim that “meritocratic” pathways (exams, promotions) were manipulated to create a pipeline for insiders. In both the French and Turkish cases, the sociological mechanism is similar: ordinary network effects—trust, shared schooling, mutual assistance—become politically reframed as “infiltration,” which then helps justify exceptional countermeasures against not only individuals but an entire community.

Stripped of their influence at home, these displaced Islamically-inspired actors began to reorganize and adapt within Western societies. By 2019, analysts noted that “a Gülenist diaspora is in the making” as many followers fled to Europe and North America, seeking the rule of law and safety of liberal democracies. Crucially, the Gülen movement in exile has doubled down on its long-standing ethos of education, interfaith dialogue, and lawful civic engagement, rather than agitating for any violent or revolutionary agenda. In fact, exile has reinforced their eager-to-integrate stance. Western observers see that Gülen-affiliated exiles present a “modern, non-violent, eager-to-integrate” profile that pointedly contrasts with more militant Islamist movements. This orientation – swimming with the tide of anti-authoritarian sentiment while upholding a peaceful, law-abiding image – has won them a degree of goodwill among Western policymakers. In other words, the experience of diaspora has accentuated their Calvinist-like pragmatism: they focus on rebuilding schools, businesses, and dialogue centers abroad, portraying themselves as model immigrant contributors rather than as aggrieved revolutionaries.

Even before 2016, Gülen’s followers were known for operating a vast network of private schools, universities, media outlets, and charities across the globe. The movement’s motto of “Hizmet” (service) encouraged members to excel in secular education and professional fields while maintaining piety – a combination often likened to the Protestant work ethic. Gülen-instilled values led devotees to pursue doctorates in science, establish companies, and donate a portion of their income to community causes. In the United States, for example, Gülen-linked educators founded high-performing charter schools and cultural centers in cities like Houston, where Turkish-American entrepreneurs support institutions such as the Turquoise Center and interfaith dialogue forums. This diaspora infrastructure, built well before the coup, reflected an implicit strategy of integration: the movement flourished within secular systems by emphasizing meritocracy, inter-cultural outreach, and respect for the rule of law – principles that resonated with Western norms.

After 2016, these tendencies only deepened. Facing vilification by the Turkish state, Gülenists in exile reside in a comfortable environment in the West, which paradoxically both protects and challenges them. On one hand, their victim status as refugees from authoritarian repression allows them to align with Western public opinion against Ankara. On the other, exile has prompted internal soul-searching within the movement – a re-examination of their past political entanglements and an emotional reckoning with questions of state, nation, and religious mission. Nonetheless, the outward strategy remains one of disciplined, principled engagement. The Gülen diaspora continues to champion education and interfaith understanding as its main public agenda. It studiously avoids any hint of violent rhetoric, positioning itself as a reformist, principle-driven Islamic voice compatible with liberal democracy.

Historical Parallels: Calvinist Refugees and Institutional Maturity

The historical episode is emblematic of how Calvinist Protestantism transformed under adversity, offering illuminating parallels to the Gülen Movement in Western diasporas, especially in Europe today. In the late 1600s, French Protestants (Huguenots) faced violent repression after King Louis XIV revoked their religious freedom. Hundreds of thousands defied a ban on emigration and fled France with little more than their skills and faith. Many were educated artisans, traders, and professionals who found refuge in Protestant-friendly countries such as England, the Netherlands, Prussia, and Switzerland. Their exile experience forged them into disciplined, industrious communities abroad. Notably, host nations soon discovered that these Calvinist refugees brought enormous socio-economic contributions. Contemporary accounts record that the loss to France was gain for its rivals: “hundreds of thousands of Protestants, many of whom were intellectuals, doctors and business leaders,” transferred their expertise to Britain, Holland, Prussia and beyond. In Brandenburg-Prussia, the Calvinist “Great Elector” Frederick William welcomed Huguenots in 1685 explicitly to help rebuild his war-torn land, granting them privileges and seeing immediate benefits. Huguenot immigrants are thought to have “contributed significantly to the development of many new industries, such as the textile industry” in Prussia. In England, Huguenot weavers, silversmiths and financiers bolstered the economy (though not without local resentments). Over a few generations, these Protestant diasporas integrated linguistically and culturally – the Huguenots in South Africa, for instance, adopted the local Dutch language within three generations – yet they also left a lasting legacy of enterprise, craftsmanship and institutional enrichment in their adopted societies.

The secret to this success was the institutional maturity and work ethic that Calvinist communities developed under pressure. Deprived of state power or majority status, they turned inward to strengthen their own networks: establishing churches, schools, mutual aid funds, and guilds wherever they settled. Calvinist theology, with its emphasis on personal diligence, frugality, and a sense of divine “calling” in one’s work, underpinned these efforts (much as Weber later theorized). But equally, practical necessity drove them to prove their value in host societies by excelling economically and abiding by laws. Charismatic leadership was less evident; instead, collective governance and adherence to doctrine held communities together. For example, the French Huguenot churches in exile often formed consistory councils to manage affairs, demonstrating self-discipline and transparency that impressed local authorities. As a result, Calvinist refugees earned a reputation as law-abiding, productive citizens, which in turn gradually improved their standing and security in host nations. By the 18th century, many descendants of Calvinist exiles rose to prominence in commerce, academia, and even government in their new homelands, effectively reshaping Protestantism into a force for socio-economic progress rather than rebellion.

This historical arc closely mirrors what we now observe with “Calvinist Islamism.” Like the Huguenots, today’s exiled Gülenists are often motivated by both faith and the practical need to survive in a new environment. They gravitate towards sectors where they can excel without provoking hostility – education, trade, science, and inter-community dialogue – much as the Huguenots gravitated to banking, crafts, and teaching. In place of Calvinist congregational schools, they build modern schools and tutoring centers; in place of guilds, they establish professional associations and charities. The guiding impulse is similar: to preserve their religious identity through constructive engagement and to demonstrate that identity’s compatibility with (even benefit to) the broader society. Just as importantly, the principle-based leadership in these contexts parallels that of the Calvinist elders or Puritan town councils. Decisions tend to be made through consultation and reference to founding ideals (such as the writings of Gülen) rather than the whims of a single leader. In the Protestant case, John Calvin’s direct influence waned as local Calvinist communities became self-regulating; in the Gülenist diaspora case, charismatic figures remain far away, especially after the passing of Fethullah Gülen in 2024, necessitating a more collective leadership. The net effect is a form of religious activism that is sober, methodical, and oriented toward gradual community uplift – much like Calvinism’s evolution from a radical reformation creed to a bedrock of bourgeois stability in Northern Europe.

Implications for Muslim Representation and Integration in the West

The rise of “Calvinist Islamism” in Western diasporas carries significant implications for how Islam and Muslims are perceived and participate in society. Firstly, these movements present a counter-narrative to the stereotype of the Muslim immigrant as either a radical or an outsider. Their visible contributions – successful businesses, high-achieving schools, humanitarian organizations – bolster the image of Muslims as integral, productive members of Western communities. For instance, Gülen-inspired schools in the United States have not only provided quality education to thousands (of many faiths) but have also engaged with local civic leaders, showcasing a model of a Muslim-run institution serving the public good. Such examples chip away at the notion that devout Muslims cannot assimilate or that Islamic values inherently conflict with Western life. On the contrary, the principled work ethic and civic responsibility emphasized by these groups resonate with core Western ideals. It is telling that Western policymakers, think-tanks, and even intelligence agencies have at times viewed movements like Gülen’s as bridges to a more moderate, democratic Islam. The diaspora context amplifies this effect: by flourishing of democracy, freedom and economic opportunity in the West, these Muslims create individuals and communities who are willing to adapt to modernity.

Secondly, the integration of Muslim diasporas gets a boost from this trend. Because “Calvinist Islamist” groups are eager to integrate and explicitly non-threatening, they often serve as intermediaries between Muslim communities and host governments. They tend to advocate for constructive engagement: voting, dialogue with officials, interfaith forums, and coalition-building with non-Muslim allies. This stands in contrast to both isolationist tendencies (enclaves turning inward) and confrontational Islamist politics. The principle-based approach means these groups focus on issues like education, social justice, or moral reform that can be pursued within existing legal frameworks.

The social, economic and political participation of Muslims in the West may also be influenced in profound ways. As these disciplined Islamist diasporas stabilize, they often cultivate educated, civically engaged second generations. Already, the ethos of service and education espoused by groups like Gülen’s has led many younger Muslims to enter fields like law, academia, and public service with confidence. Their formative experiences in diaspora institutions (weekend schools, youth groups, business associations) instill both a strong Muslim identity and a commitment to pluralistic society. This mirrors how Protestant dissenters, once integrated, contributed disproportionately to democratic development – for instance, many Enlightenment thinkers and early American statesmen had Puritan or Huguenot roots. Likewise, a Muslim middle class influenced by Calvinist Islamist values could become a backbone for greater Muslim civic leadership in Western countries

These developments may have implications for the home country—Turkey—from which this movement came. History shows that diaspora success stories can exert influence back home over time – Huguenot prosperity abroad was one factor that eventually pressured France to reconsider its policies (leading to partial tolerance in 1787). Similarly, if exiled Islamist groups thrive in the West by being peaceable and productive, they set an example that challenges the authoritarian narratives in their countries of origin. For instance, the Turkish government’s portrayal of Gülenists as irredeemable “terrorists” is harder to sustain if Western observers see those same people as diligent teachers and law-abiding neighbors. Over the long term, the diaspora could become a lobby for political reform in their homelands, advocating principles of pluralism and rule of law that they have embraced abroad. This is not guaranteed – some exiles remain consumed by exile politics or become detached from their roots – but the possibility exists for a positive feedback loop: Western-based Islamist reformers helping to liberalize Eastern polities, much as Calvinist refugees from England (the Puritans) influenced debates on religious freedom and governance in 17th-century Europe.

By: GEOPOLIST – Istanbul Center for Geopolitics