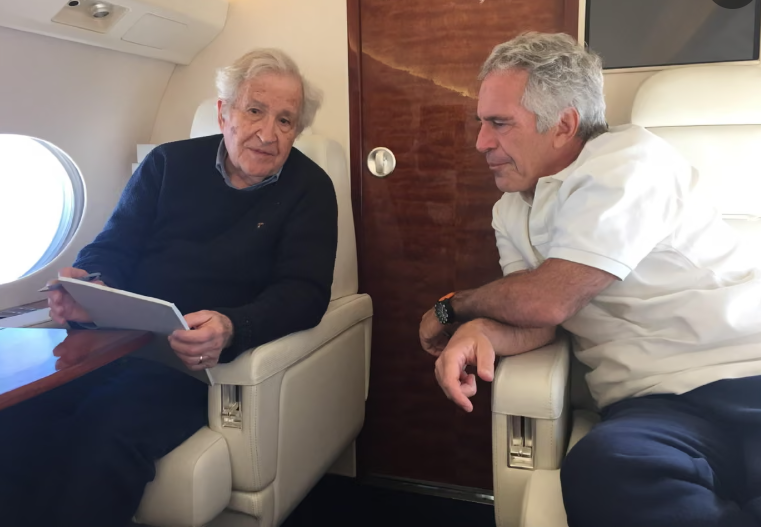

For decades, Noam Chomsky has been more than an author. He has been a moral reference point—an intellectual who taught generations of readers, students, and journalists to interrogate power, decode propaganda, and distrust the flattering self-portrait that empires paint of themselves. That’s precisely why the recent revelations tied to Jeffrey Epstein have landed as something more than celebrity-gossip collateral damage. For many admirers, it feels like betrayal by method: the critic of elite impunity appearing, at minimum, uncuriously comfortable in the orbit of a man whose entire life was built on elite impunity.

The latest disclosures are part of a massive public release pushed by the U.S. Department of Justice under the “Epstein Files Transparency Act,” with the department saying it posted millions of pages of material on January 30, 2026. That flood of documents has generated scandal across politics, business, academia, and royalty—not because being named is proof of a crime, but because the files illustrate how long, and how casually, relationships with Epstein often persisted even after his 2008 conviction.

The “Clean Slate” Defense—and Why It Collapses Here

The most damaging material isn’t a claim that Noam Chomsky participated in Epstein’s crimes; reputable reporting has not made that allegation. The problem is judgment—and the public posture that accompanied it.

When asked in 2023 about meetings with Epstein after Epstein became a registered sex offender, Chomsky replied that it was “none of your business,” acknowledged meeting him, and argued that serving a sentence should restore a “clean slate.” Even if one accepts the legal premise (which is itself contestable in cases involving sexual exploitation and power), the argument fails on Chomsky’s own terrain. This isn’t a private citizen’s awkward friendship. This is a world-famous critic of structural abuse, hierarchy, and institutional shielding of predators—choosing to treat a convicted sexual offender as an ordinary social contact, and treating public scrutiny as impertinence.

It is exactly the kind of “access logic” Chomsky spent a lifetime warning others about: the quiet internal bargain where proximity to influence is rebranded as “just conversation,” and moral red lines dissolve into professional or intellectual curiosity.

What the New Material Suggests: Familiarity, Not Distance

The newer tranche does not read like a cold, transactional relationship that can be filed under “networking.” Reporting on the newly released documents describes warm social planning, personal familiarity, and an ease that sits uneasily alongside the public image of principled distance.

The most corrosive detail is the tone attributed to Chomsky in a message Epstein forwarded to an associate in 2019—advice on how to respond to public scrutiny. According to the reporting, the guidance was essentially to ignore the press storm, accompanied by a remark framing the moment as “hysteria” around abuse allegations. If accurate, that line is not a minor rhetorical slip. It sounds like contempt for the social fact that survivors and the public were finally refusing to normalize powerful men’s sexual violence as background noise.

For many readers who built parts of their own moral vocabulary through Chomsky—about power, coercion, and institutions that launder wrongdoing—the dissonance is visceral.

The Steve Bannon Angle: When Epstein Becomes the Social Broker

Then there is the detail that turns this from “unfortunate acquaintance” into something more revealing about how Epstein operated.

In the newly surfaced material, Chomsky is reported to have contacted Steve Bannon—a figure associated with hard-right, nationalist politics—seeking an introductory meeting, explicitly noting that Epstein provided Bannon’s contact information.

This matters for two reasons.

First, it shows Epstein functioning not merely as a disgraced financier with a dark private life, but as a connector—someone who could shuttle between ideological camps and offer introductions that flatter the recipient with the feeling of being “important enough” to be networked at that level.

Second, it punctures the most generous interpretation of Chomsky’s relationship with Epstein as purely “business” or “intellectual conversation.” If your convicted-sex-offender friend is also your bridge to meetings with political power brokers, then you are not merely “talking to everyone.” You are accepting the utility of the very social machinery that predators like Epstein exploited: status exchange.

Epstein’s network can be understood as a form of reputational arbitrage—a “social Ponzi scheme” in which being associated with famous individuals leads to even more famous connections. This dynamic turns social affiliation into a form of protection. In this sense, every notable figure who considered Epstein a suitable dinner companion inadvertently became part of this mechanism, regardless of their intentions.

The Lasting Damage: Not “Guilt,” but Hypocrisy

Supporters will argue—correctly—that correspondence and meetings are not proof of criminal complicity, and that Chomsky’s long-standing habit was to engage almost anyone who approached him. Even sympathetic takes concede, however, that the association is shocking because it collides with Chomsky’s worldview: the critic of elite corruption appearing naïve about how elite corruption recruits legitimacy.

And that is why this episode cuts deeper than a typical scandal. Chomsky’s work was built on a demand for consistency: scrutinize power, question narratives, follow the incentives. Yet in Epstein’s case, the incentives were almost painfully obvious—money, access, prestige, insulation—and the narrative was the easiest in the world to see through: the “misunderstood genius” benefactor who just happened to collect important friends.

Many public figures caught in Epstein’s orbit have attempted the standard script: regret, distance, ignorance. Chomsky’s earlier response did the opposite—defiance, minimization, and a legalistic “clean slate” framing. That posture has now become part of the story, compounding the disappointment: not only bad judgment, but a refusal to treat public concern as legitimate.

A Brutal Irony

Chomsky spent a lifetime describing how institutions manufacture consent—how elite systems normalize the unacceptable by controlling frames, gatekeeping language, and policing what is “appropriate” to question. The Epstein saga is, in miniature, a case study in that same normalization: influential people persuading themselves that the predator is “complicated,” that the association is “just social,” that critics are “hysterical,” that reputations can be compartmentalized.

The tragedy is not simply that a revered intellectual was linked to a notorious predator. It’s that the linkage looks, from the outside, like the very kind of elite social compromise his readers trusted him to resist.

If Noam Chomsky had met Jeffrey Epstein much earlier in his life—decades before the documented contacts in his late 80s—it is likely that public perception of that relationship would have been far harsher, and Chomsky might well have faced accusations of complicity or involvement in sexual offenses on the same terms as many other powerful figures who became embroiled in Epstein’s orbit.